Review Essay: On Making European Cult Cinema (Part II)

/What follows is the second part of a review essay written by Billy Proctor and addressing some core debates in the fields of cult media and fandom studies.

As the chapters proceed in Making European Cult Cinema, Carter eventually comes onto the object of study, European Cult Cinema (85), and makes yet another outlandish claim. This time it is cult media studies that comes within his rifle-sights, but his pop-shots are again quite easily knocked aside. Like fan studies, cult media scholars are culpable in celebrating the object of study as a symptom of the scholarly attempt to push ‘trash cinema’ into academic purview, an attempt that, Carter argues, continues to be conducted by ‘fancademics’ in ways that valorize fan objects. But in order to do so, Carter once again misses key literature that would undermine his points about this so-called ‘fancademia.’

Take Carter’s brief rejection of the label ‘trash,’ which he argues comes out of academic discourse. This is factually inaccurate. In Chapter Three, Carter suggests that an early use of the term ‘trash’ as a label for low-budget cult cinema emerges can be found as far back as Pauline Kael in 1968 (86). Yet Pauline Kael is not an academic, but a renowned film critic, hence more a journalistic discourse than an academic one (if that is indeed the origin of the term as it pertains to cult cinema, which is surely worth investigating further). Carter argues that ‘Fancademics use the academic discourse of trash to justify the value of studying cult film while fans employ the word “cult” as a way to give their fan object greater aesthetic validity’ (87-88).

For fans, the word trash is problematic. As the academic use of the term has increased, it has been rejected by fans because of its derogative, disrespectful connotations. Evidence of this rejection can be found in the many fan blogs and message board responses to the release of European cult film Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977) on DVD and Blu-Ray by the British Independent DVD label CineExcess. Fans objected to the use of the subtitle “taking trash seriously’ found on the front cover, believing it to be, as described by one fan, “borderline offensive.” Such reactions seem to be a labelling of the fan object as trash (87).

It is more than likely that the fan rejection of the ‘trash’ signifier here is primarily because it is attributed to Suspiria, rather than cult cinema in general, as the film invariably considered to be Dario Argento’s crowning masterpiece, a director that has been viewed as ‘the Hitchcock of Italian Cinema.’ Of course, Carter would no doubt argue that valorizing Argento as ‘auteur’ would be to fall into the ‘fancademic’ trap, but it is not only academics that have suggested that the director isn’t ‘trashy,’ but part of a broader discursive cluster, supported by Brigid Cherry’s analysis of fan discourses which suggests that Suspiria represents the apotheosis of Italian cult cinema (2012), a sentiment articulated by Carter later in the book: ‘Suspiria is probably the most celebrated of these films’ (185). I feel the same way about Mario Bava, especially Blood and Black Lace, if I’m honest, while I’m more than happy to recognize Lucio Fulci’s work as trash cinema, which isn’t to say I don’t enjoy his films (but that’s a ‘fancademic’ perspective I guess!) What I mean to say is that the example of fan complaints about Suspiria being branded trash cinema is because Argento is held in high esteem as a canonical visionary artist by fans, film critics, and, yes, by academics. Carter is correct that ‘in the DVD age…the dominant discourse has become that of “art object”’ (87), but this discourse is not a simple matter of a fan/ academic binary. This understanding of ‘cult-as-art’ is part and parcel of industrialized brand discourses, what David Church (2015) describes as a ‘genrification’ process, strategized by media companies such as Arrow—amazingly left out of Carter’s analysis except for a brief mention in the conclusion—that discursively transform ‘trash cinema’ into ‘art-objects’ via material-object practices like lavishly designed box-sets filled with special features, interviews, director’s commentaries, and 4K transfers. From this perspective, it is not only that ‘fan discourses circulated in fanzines, magazines, and online fora tend to treat the films as art cinema rather than trash’ (87), but also as an economic strategy adopted and maintained by ‘genrified’ DVD/ Blu-Ray distributors. In doing so, these brand discourses and distribution strategies conduct a flattening of cultural distinctions between so-called ‘high art,’ and ‘trash cinema,’ as Mark McKenna argues:

Though a gamut of companies operate within this market, these marginal offerings can be most easily understood as being located in what has historically been considered opposite ends of the spectrum. First, that of high art: the worthy, canonical films of academia, often art-cinema or films of perceived artistic merit that have been judged to have a significant cinematic value. Second, and at the other end of the spectrum sit low culture, trash or ‘B’ movies— films perceived as having very little artistic merit which often revel in sex or violence and can collectively be grouped under the umbrella of exploitation or cult movies. Though processes of cultural distinction have historically separated these cinemas based upon preconceived valorisations, in recent years an increased convergence of these markets has been observed. This is largely commercially driven, with distributors reinforcing, extending and challenging traditional notions of what might constitute the canonical film, and consequently further augmenting how ideas of value are constructed for films which fall outside mainstream consumption (2017).

Hence, the artistic legitimation of trash cinema by DVD/ Blu-Ray distributors shares characteristics with the cultural distinctions appended to ‘prestigious’ boutique releases by Criterion, working to collapse the ‘high art/ low trash’ binary as an economic strategy, and one which many fans embrace in droves. Joan Hawkins has also shown how art cinema and trash objects sat side-by-side in video catalogues during the 1980s and 90s, whereby ‘the design of the catalogs also enforces a valorization of low genres and low generic categories,’ challenging ‘many of our continuing assumptions about the binary opposition of prestige cinema (European art and avant-garde/ experimental films) and popular culture’ (3).

In the world of horror and cult film fanzines and mail-order catalogs, what Carol J. Clover calls “the high-end” of the horror genre mingles indiscriminately with the “low-end.” Here, Murnau’s Nosferatu (1921) and Dreyer’s Vampyr (1931) appear alongside such drive-in favorites as Tower of Screaming Virgins (1971) and Jail Bait (1955). Even more interesting, European art films that have little to do with horror— Antonioni’s L’avventura (1960), for example—are listed alongside movies that Video Vamp labels “Eurociné-trash” (2000, 3-4).

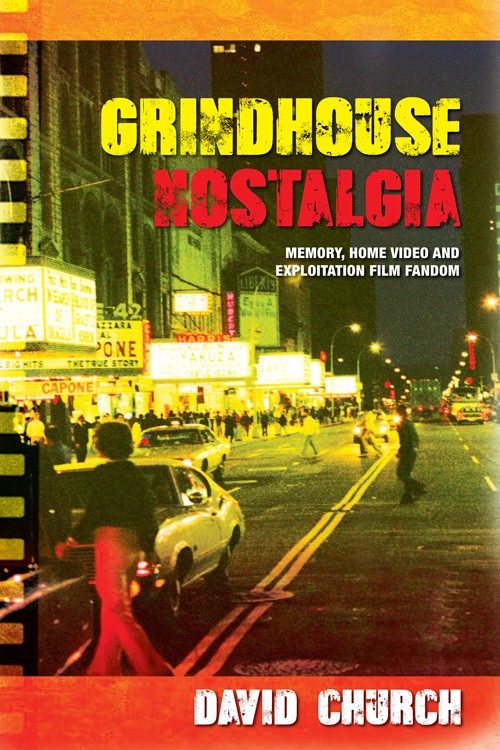

Carter effectively constructs a ‘moral dualism’ (Hills 2002) between ‘trash’ as a ‘bad’ academic term, and ‘cult’ as a ‘good’ fan term, in essence rejecting the former and unwittingly buying into a valorization of the fan-object, begging the question as to whether Carter ends up in a hermeneutic trap of his own making as a ‘fancademic’ himself (which I come onto below). But he again undermines this argument several times by openly saying that his first confrontation with the term ‘trash’ as a cult cinema fan himself comes not from academia but a fan publication, European Trash Cinema, ‘one of the earliest fan publications to focus exclusively on European Cult Cinema’ (86)—which is also the focus of Antonio Lázaro-Reboll’s ‘Making Zines: Re-Reading European Trash Cinema’ (2016), another academic publication that Carter does not consult despite the argument sharing profound similarities regarding the way in which fans ‘contributed to the circulation, reception and consumption of European horror film’ (1)—and later in the book, Richard Green’s Confessions of a Trash Fiend (105). Film historian Guy Barefoot identifies trash’s origins in fan discourse in publication such as Trash City, Trashola, Trash Compactor, and Asian Trash Cinema (2016, 2017). In more contemporary terms, there is the Trash Cinema Festival[1], film screenings such as Stacey Case’s Trash Palace[2] or Hamilton’s Trash Cinema[3], and online recommendations for trash films[4], and other examples (far too many to list here exhaustively). Thus, trash is neither valorized nor rejected by fans, but is part of a broader discursive field with utterances emanating from several quarters (journalism, film criticism, fan publications and practices as well as academic literature). In fact, in an empirical study of trash fans, Keyvan Sarkhosh and Winfried Menninghaus found that the label ‘trash’ was widely endorsed by fans, thus ‘underlying the positive use of the label, i.e on how something can be identified as cheap and worthless “trash” and still be embraced and (re-)evaluated as providing positive enjoyment’(2016). The point here is that trash is in no way, shape or form a product of ‘fancademic’ discourse, and even when used for scholarly purposes, it is to theorize and conceptualize it as a ‘reading protocol,’ an ironic positioning that some fans embrace and some don’t, as David Church complicates in Grindhouse Nostalgia: Memory, Home Video and Exploitation Film Fandom (2015).

For Carter to make the claim that ‘the study of European cult cinema has been dominated by fancademic work’ (97) that celebrates the object in the same manner that a fan would, he needs to circumnavigate literature that would complicate that perspective, especially in relation to Italian cult cinema, the focus of Carter’s book. Indeed, Carter explains that his focus is more on fan enterprises related to the Italian genre known as the giallo, so effectively, the book’s title should perhaps have been revised from Making European Cult Cinema to Making Italian Giallo Cinema. But I want to look more closely at this concept of the ‘fancademic’ to fully understand what Carter means before moving on.

How is ‘fancademic’ different to Jenkins’ ‘aca-fan’ (1992) or Hills’ ‘scholar-fan’ and/ or ‘fan-scholar’? Carter claims that ‘fancademia’ is also where fan and scholar collide, but the way in which it is framed seems to illustrate that it is the academic side of the identity that is taking control, lionizing and celebrating the fan object without being necessarily self-reflexive enough, so that scholar-fans are now more likely to be better identified as fan-scholars, which ‘can lead to academic work that is the product of the author’s fandom’ (19). My reading of Carter is that ‘fancademic’ work is when a fan object is unduly celebrated by scholars and that this can take different routes. Firstly, to view fan production as a form of symbolic resistance to dominant ideologies and meanings is celebratory because it excludes consideration of economic factors and the conditions with which fan productions come to be made. (We have already seen how this is a fallacious assertion.) Secondly, in relation to cult film, ‘the majority of “fancademic” work [tends towards] textually analyzing European cult film, without investigating or problematizing either the fandom that surrounds it or the process through which the fan object was delineated’ (85), which ‘has meant that attention has been placed on the text rather than considering its consumption, or more specifically, its fandom’ (90). Carter goes onto claim that ‘Italian cult cinema is often ignored in academic studies of the Italian film industry or is relegated to a brief mention’ (93). This is untrue. There are multiple works that do not simply analyze ‘the text,’ but which assuredly address the cultural, economic and political contexts in which cult films were produced, most certainly not ‘relegated to a brief mention’ (for example see: Allmer et al 2012; Baschiera 2017; Baschiera & Hunter 2016; Bondanella and Pachionni 2017; Fisher 2011; Fisher and Walker 2017; Hunter 2016; Hunter 2017; Kannas 2017; Platts 2017; Totaro 2011; Wagstaff 1992; Wagstaff 1998). Thirdly, Carter suggests that ‘fancademic’ work tends to also focus on single directors, or auteurs, and as a consequence, ends up producing valorizations and celebrations of cult cinema (94) in the same manner by which fans do. Yet Carter argues that British fan publishing house FAB press ‘is a publisher of fancademic work’ (94), within which ‘the writing style is semi-academic, attempting to critically interrogate film’ (133). Taking all of this together, then, I suggest that the concept of the ‘fancademic’ should be rejected before it gets off the ground as it definitionally and semantically replicates the term ‘scholar-fan’ without further interrogation. More than this, however, is that Carter seems to unwittingly equate fan studies and cult media studies scholars with ‘semi-academic’ fan publications like FAB Press, by extension accusing scholars of being ‘half’ academic! Thus, being a ‘fancademic’ means one’s focus is on either of these four options, each of which are nothing but celebratory: a/ marshaling fan activities as symbolically resistance; b/ conducting textual analysis; c/ examining the work of single directors, thus elevating cult filmmakers to the status of auteur; and d/ who do not include production and consumption in their exegesis.

But of course, Carter is neither ‘fancademic,’ scholar-fan nor aca-fan (or at least he doesn’t identify clearly as one or the other). That’s not problematic in and of itself; I don’t identify as such either. In fact, I share Will Brooker’s distaste regarding the label ‘aca-fan’:

As the term is taken to mean fans of popular culture—often, more specifically, science fiction, superheroes and fantasy, I think—who write critically about something they love, and about the communities around it, often but not always including an exploration of their own fan identity and their attachment to the fan object. That is what we tend to mean by it, but we could also consider that Shakespearean scholars are also, no doubt, fans of Shakespeare—the same must be true of most scholars of Dickens or Austen. Academics who write about politics are surely fascinated by politics and follow it in the same way as someone else might follow Star Trek through routine patterns of viewing, through discussion, through communities and gatherings…I suspect most math scholars love mathematics (2018, 64).

Naturally, we might expect the age-old distinctions between ‘high art’ and ‘low culture’ to be maintained by scholars of Shakespeare, Dickens and Austen, but does this also not risk effectively reproducing those same cultural distinctions by insisting that fan identities need to be laid out naked for all to see, especially if it is only a small portion of the academic population that does so? I would not have considered myself a fan of superhero comics when I started my PhD thesis on reboots, even though comics were a big part of my childhood. Yet as I poured over thousands of comics during research, and spoke to many academics and fans about the forces and factors that underpinned their continued publication after the better part of a century, as well as favorite titles and characters etc., I similarly grew to enjoy certain authors, artists and stories, so much so that I continued to read comics after my PhD was completed (although to be fair, I have written on comics outside of that research and am currently writing a monograph based on my PhD). Am I a fan? And is it possible to isolate out the complexities that make me ‘me,’ whether by claiming I’m an academic first and a fan second, or dealing with the other multiple identities that combine and coalesce to form ‘the self’? Do I have to identify as a fan because I have parted with a lot of cash over the years by spending on comic purchases? (And it is a lot of money, I admit.) But I spend a lot more money on academic books, so am I safe in accepting that I do this for scholarly reasons and ignore the fun I have along the way? I read recently that Umberto Eco was inspired to study comics, taking ‘his collection of two or three hundred issues of Superman out of his cupboard and used it to write the first critical article on American comic books’ after reading the following injunction by Edgar Morin:

It is also essential for the observer to participate in the object of his observation’ one must, in a way, enjoy oneself at the movies, be fond of inserting coins into jukeboxes, have fun with slot machines, keep up with games on the radio and television, hum the latest tune. You have to somehow be one of the crowd, at the dance, among onlookers, or at sports events yourself. You have to enjoy strolling along the boulevards of mass culture (quoted in Gabilliet 2010, xix-xx)

(I’m sure I wouldn’t lump Eco in with the ‘fancademic’ label though.)

Oliver Carter does admit that he is an academic and a fan of cult cinema, however, yet he also argues that his fandom is an advantageous characteristic, which is precisely what Jenkins argued in 1992! However, Carter pursues the idea that his fandom does not colonize his academic identity like it does with ‘fancademics,’ arguably meaning that many ‘aca-fans’ should perhaps be understood as ‘fan-scholars’ with the fan identity taking over and celebrating the object of fandom at the expense of academic rigor and theoretical control. That isn’t only disrespectful but incredibly arrogant, effectively running the risk of setting up a ‘me-versus-them’ dichotomy that is difficult to escape from. In effect, Carter seems to imply that he is an academic first and foremost; a fan second; and definitely not a ‘fancademic,’ or a ‘semi-academic.’ I would not presume to argue one or the other for Carter as it is, in many ways, irrelevant. But I admit to thinking that the way in which he does claim that certain disciplines are awash with ‘semi-academics’ is not productive.

I wonder why Carter felt that constructing definitive statements and casting specious claims all over the place would be the best way to support his central argument, especially considering that it often undermines itself. As we move into Chapter Four, Carter turns a corner, although the latter half of the book is not without its problems, mainly due to a distinct lack of theorization around the principles of virtual ethnography and auto-ethnography as well as the economic dialectics between “formal” and “informal” industries. Indeed, I would argue that Carter’s case studies may be framed as enacted through hegemonic processes of ‘resistance and incorporation,’ and that this could have added some theoretical meat to the bones of the argument.

The first case studies are historical examples, looking to three fan companies which produced fanzines, magazines, books, and films, clearly establishing that much hard work, love, money, and risk, go into alternative economic practices. The ‘semi-academic’ publication house, FAB Press, which is deemed as such because ‘[n]umerous articles draw on psychoanalysis, cite academic work and are fully referenced’ (133), publications that ‘would be fancademic, textually and contextually analyzing cult films and using citations’ (134), meaning that we can also lump legitimate academic studies that draw on psychoanalytic frameworks or other contexts as celebratory (one would be forgiven for wondering what approaches would not be viewed as fannish celebrations at this point, although I am not a lover of psychoanalysis by any means). But what is interesting about FAB Press is that creator Harvey Fenton ‘moved from being a sole trader to establishing FAB Press as a limited company’ (135), which demonstrates a moving-between the ‘informal’ alternative economy, and the ‘formal’ structures of neoliberal capitalism. This maneuver should not be taken as a sign of distinct economic spheres as Fenton would also sell FAB products out of shops, like Forbidden Planet, or on websites such as Amazon, before he established FAB Press as a limited company, emphasizing the dialectical relationship between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ economies. It seems to me that what is being described here are processes of hegemony, whereby ‘resistance/ incorporation’ are not binary spheres, but interlocking forces dialectically and dialogically interfacing with one another.

In Chapter Five, Carter moves to a case study which is more contemporaneous, considering the way in which fans conduct illegal practices on a Torrent site to share, upload, and download giallo films as part of a living digital project, ‘as a factory for fan production’ where members ‘receive no obvious financial reward for their production’ (140), but instead, run the site as a gift economy, with numerous reciprocal transactions taking place whereby users accumulate symbolic tokens, identified as ‘Cigars,’ the credit value of which ‘can be used to purchase different items such as upload credit, lottery tickets (to win a large amount of upload credit), and to make requests for specified content to be uploaded to the site by other members’ (147). In my reading, this convincingly lays out that symbolic tokens operate simultaneously as fan subcultural capital, which as Carter puts it, ‘the more cigars a user has, the greater standing they have within the community’ (147) (although that is my reading, not Carter’s).

But Carter makes yet another bold claim, that ‘commercial DVD releases of gialli have slowed’ in the UK and USA (140), which is demonstrably false. The aforementioned Arrow as well as other DVD/ Blu-Ray companies such as 88 Films, have been producing and distributing Italian cult cinema objects in boutique forms at an accelerated pace, and the availability of gialli and Italian horror etc. has never been so healthy in UK and USA markets—although it is difficult to ascertain which gialli as rare and unavailable as Carter doesn’t mention which films he is speaking of (although he does mention Red Light Girls [1974], which has not yet received boutique treatment as far as I’m aware). In addition, Iain Robert Smith has also written on the very same website, but this is neither discussed nor cited (2011).

With that said, I found this chapter to be engaging, providing the most valuable insights regarding the alternative economy, with fans actively breaching copyright legislation and risking criminal prosecution in order to support distribution of fan objects. In many ways, it is fandom as outlaw, the internet as wild west, and file-sharing sites as saloon. But even within this digital frontier, there are Sheriffs in town. As Carter addresses, the hierarchies in place on the site ‘reproduces formal political and economic conditions in order for the site to function, operating as if it were factory of fan production’ (163). (I admit that I found it ironic that Carter cites Jenkins’ Textual Poachers in this chapter to support several points, literally drawing upon what he sees as ‘fancademic’ work.)

The final chapter on fan enterprises is also insightful, moving onto fans who produce T-shirts, again transgressing, or at the very least subverting, the legalities of copyright. Carter then performs a unique maneuver whereby he recounts the production process centered on fan t-shirt manufacturing by utilizing the services of Spreadshirt himself to create giallo branded garments. Although Carter’s auto-ethnographic account could definitely use stronger theorization, it is a distinctive approach that will be very informative for readers interested in the methods and modes of fan productions that use ‘formal’ outlets to produce ‘informal’ products, again stressing the dialectics between alternative and legal economic spheres (which would probably be best to view as interlocking Venn diagrams than discrete entities).

In the conclusion, Carter considers the rise of Crowdfunding, with the emergence of internet portals that allow fans to raise finances for fan productions of various kinds (the most famous example perhaps being Kickstarter). Narrativizing the way in which one fan managed to raise funds for a documentary film, Eurocrime (2015), which focuses on the politziotteschi cycle of Italian cult crime films, and managed to reach its goal, now available to purchase in the formal economy.

There is much to admire about the book’s later chapters, especially when Carter turns to his case studies, but in the conclusion, he raises hackles again by repeating his insistence that ‘fan studies needs to further consider the economic processes that are involved in fan activity, moving away from the celebratory, fancademic studies’ (198). Again, I’m not quite sure why Carter set out his stall so aggressively, especially when lacking solid epistemological foundations. If nothing else, Making European Cult Cinema: Fan Enterprise in an Alternative Economy will no doubt spark further debate about the claims made within as it pertains to fan studies and cult media studies, but I would also encourage interested readers from those disciplines, and perhaps other fields, to consider the valuable insights brought out by Carter’s investigation into fan enterprises. There are many fruitful aspects that will no doubt support and enhance scholarly thinking on the topic, and that should not be denied either.

References

Allmer Patricia, Brick, Emily, & Huxley, David. 2012. European Nightmares: Horror Cinema in Europe Since 1945. London/ New York: Wallflower Press.

Bakioğlu, Burcu S. 2016. ‘Exposing convergence: YouTube, fan labour, and anxiety of cultural production in Lonelygirl15,’ Convergence: The Journal of Research into New Media Technologies; Apr2018, 24(2), p184-204.

Ball, Kevin D. 2017. ‘Fan labor, speculative fiction, and video game lore in the "Bloodborne" community,’ Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 25.

Barefoot, Guy. 2017. Trash Cinema: The Lure of the Low. New York: Wallflower Press.

Baschiera, Stefano & Hunter, Russ. 2016. Eds. Italian Horror Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Baschiera, Stefano. 2017. “Streaming Italian Horror in the United Kingdom: Love Film Instant,” The Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 5(2): 245-260.

Blodgett, Bridget & Salter, Anastacia. 2017. Toxic Geek Masculinity in Media: Sexism, Trolling, and Identity Policing. London/ New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bondanella, Peter & Pacchioni, Federico. 2017. A History of Italian Cinema (second edition). London/ New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Brooker, Will. 2001. Batman Unmasked: Analysing a Cultural Icon. London: Continuum.

Brooker, Will. 2014. ‘Going Pro: Gendered Responses to the Incorporation of Fan Labour as User-Generated Content’. In Wired TV: Laboring Over an Interactive Future edited by Denise Mann, pp. 72-97. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Busse, Kristin. 2009. “Fandom and Feminism: Gender and the Politics of Fan Production,” Cinema Journal 48(4).

Busse, Kristin. 2013. ‘Geek hierarchies, boundary policing and the gendering of the ‘good’ fan,’ Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies,’ 10(1). http://www.participations.org/Volume%2010/Issue%201/6%20Busse%2010.1.pdf

Busse, Kristin. 2015. ‘Fan Labor and Feminism: Capitalizing on the Fannish Love of Labor,’ Cinema Journal 54(3).

Cherry, Brigid. 2011. "Knit One, Bite One: Vampire Fandom, Fan Production and Feminine Handicrafts." In Fanpires: Audience Consumption of the Modern Vampire, edited by Gareth Schott and Kirstine Moffat, 137–55. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing.

Cherry, Brigid. 2016. Cult Media, Fandom and Textiles: Handicrafting as Fan Art. London: Bloomsbury.

Chin, Bertha. 2013. "The Fan–Media Producer Collaboration: How Fan Relationships Are Managed in a Post-series X-Files Fandom." Journal of Science Fiction Film and Television 6 (1): 87–99.

Chin, Bertha. 2014. ‘Sherlockology and Galactica.tv: Fan sites as gifts or exploited labor?’, Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 15. https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/513

Chudoliński, Michał. 2014. ‘Interview with Henry Jenkins, George Ritzer, and Mark Deuze about Popular Culture Prosumption’, Prosumption in the Pop Industry: An Analysis of Polish Entertainment Industries. Available at: http://wiedzalokalna.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2014/01/FWL_Prosumption_Report_English.pdf.

Click, Melissa. 2009. ‘“Rabid,” “Obsessed,” and “Frenzied”: Understanding Twilight Fangirls and the Gendered Politics of Fandom,’ Flow, December (https://www.flowjournal.org/2009/12/rabid-obsessed-and-frenzied-understanding-twilight-fangirls-and-the-gendered-politics-of-fandom-melissa-click-university-of-missouri/)

Coppa, Francesca, & Russo, Julie Levin. 2012. “Fan Remix/ Video,” Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 9. https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/issue/view/10

Fisher, Austin. 2011. Radical Frontiers in the Spaghetti Western: Politics, Violence and Popular Italian Cinema. London: I.B Taurus.

Fisher, Austin & Walker, Johnny. 2017. Eds. “Italian Horror Cinema,” The Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 5(2): 153-157.

Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. 2010. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of Comic Books. Translated by Bart Beatty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: University of Press Mississippi.

Godwin, Victoria M. 2016. ‘Fan pleasure and profit: Use-value, exchange-value, and one-sixth scale action figure customization,’ Journal of Fandom Studies 4(1).

Gramsci, Antonio. 1978. Selections from Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Gray, Jonathan. 2003. “New Audiences, New Textualities: Anti-Fans and Non-Fans,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6(1): 64-81.

Gray, Jonathan, Sandvoss, Cornel, & Harrington, Lee. C. 2007. Eds. Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (First Edition). New York: New York University Press.

Gray, Jonathan, Sandvoss, Cornel, & Harrington, Lee. C. 2017. Eds. Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (Second Edition). New York: New York University Press.

Hassler-Forest, Dan. 2016. Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Politics: Transmedia World-Building Beyond Capitalism. New York: Rowman Littlefield.

Hawkins, Joan. 2000. Cutting -Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-Garde. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Hebdidge, Dick. 1979. Subcultures: The Meaning of Style. New York/ London: Routledge.

Helleckson, Katherine. 2009. ‘A Fannish Field of Value: Online Fan Gift Culture,’ Cinema Journal 48(4).

Helleckson, Katherine. 2015. ‘Making Use of: The Gift, Commerce and Fans,’ Cinema Journal 54(3).

Hills, Matt. 2002. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge.

Hills, Matt. 2005. “Negative Fan Stereotypes (‘Get a Life!’) and Positive Fan Injunctions (‘Everyone’s Got to be a Fan of Something!’): Returning to Hegemony in Media Studies,’ Spectator 25(1), pp. 35-47.

Hunter, Russ. 2016. “Horrically local? European horror and regional funding initiatives,” Film Studies 15(1), pp.66-80.

Hunter, Russ. 2017. “‘I have a picture of the Monster! Il mostro di Frankenstin and the search for Italian horror cinema,” Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5(2), pp. 159-172.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2014. “Rethinking Rethinking Convergence Culture,” Cultural Studies 28(2): 267-297.

Jenkins, Henry, Ford, Sam and Green, Joshua. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked World. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry, Shresthova, Sanghita, Gamber-Thompson, Liana, Klinger-Vilenchik, Neta and Zimmerman, Arely, M. 2016. By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. New York: New York University Press.

Johnson, Derek. 2013. Media Franchising: Creative License and Collaboration in the Culture Industries. London: New York University Press.

Jones, Bethan. 2014. ‘Fifty shades of exploitation: Fan labor and Fifty Shades of Grey,’ Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 15. https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/501

Jones, Bethan. 2015. ‘My Little Pony, Tolerance is Magic: Gender Policing and Brony Anti-Fandom,’ The Journal of Popular Television 3(1): 119-25.

Kannas, Alexia. 2017. “All the colours of the dark: film genre and the Italian giallo,” The Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 5(2): 173-190

Kozinets, Robert. 2014. “Fan Creep?: Why Brands Need Fans.” In Wired TV: Laboring Over an Interactive Future edited by Denise Mann, pp. 161-175. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lothian, Alexis. 2009. ‘Living in a Den of Thieves: Fan Video and Digital Challenges to Ownership,’ Cinema Journal 48(4).

Lothian, Alexis. 2015. ‘A Different Kind of Love Song: Vidding Fandom’s Undercommons,’ Cinema Journal 54(3).

Olds, Kirstin. 2015. ‘Fannies and fanzines: Mail art and fan clubs in the 1970s,’ Journal of Fandom Studies 3(2).

McRobbie, Angela. 1994. Postmodernism and Popular Culture. London: Routledge.

McKenna, Mark. 2017. “Whose Canon is it Anyway?: Subcultural Capital, Cultural Distinction and Value in High Art and Low Culture Film Distribution.” In Cult Media: Re-Packaged, Re-Released, Re-Stored, edited by Jonathan Wroot and Andy Willis, pp. 31-49. London: Palgrave.

Milner, R. M. 2009. "Working for the Text: Fan Labor and the New Organization." International Journal of Cultural Studies 12 (5): 491–508.

Morley, David. 1992. ‘Populism, Revisionism and the “New” Audience Research’, Poetics, 21(4), pp. 339 – 344.

Platts, Todd. K. 2017. “A comparative analysis of the factors driving film cycles: Italian and American zombie film production, 1978–82,” The Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies 5(2): 191-210.

Proctor, William & Kies, Bridget. 2018. Eds. ‘Toxic Fan Practices,’ special section in Participations: The Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 15(1), May .

Regin, Nancy. 2012. Ed. ‘Fan Works and Fan Communities in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 6.

Rehak, Bob. 2014. ‘Materiality and Object-Oriented Fandom,’ Transformative Works and Cultures. Volume 16.

Robert-Smith, Iain. 2011. “Bootleg Archives: Notes on BitTorrent Communities and Issues of Access,” Flow TV.

Sandvoss, Cornel. 2005. Fans: A Mirror of Consumption. London: Polity Press.

Sandvoss, Cornel. 2011. "Fans Online: Affective Media Consumption and Production in the Age of Convergence." In Online Territories: Globalization, Mediated Practice, and Social Space, edited by Miyase Christensen, André Jansson, and Christian Christensen, 5–54. New York: Peter Lang.

Sarkhosh, Keyvan & Mennighaus, Winfried. 2016. “Enjoying Trash Films: Underlying features, viewing stances, and experiential response dimenions,” Poetics Volume 57. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304422X16300821

Scott, Suzanne. 2009. “Repackaging fan culture: the regifting economy of ancillary content material,’ Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 3.

Scott, Suzanne. 2015. ‘“Cosplay is Serious Business: Gendering Material Fan Labor on Heroes of Cosplay,’ Cinema Journal 54(3).

Stanfill, Mel. 2015. ‘Spinning Yarn with Borrowed Cotton: Lessons for Fandom from Sampling,’ Cinema Journal 54(3).

Stanfill, Mel and Condis, Megan. 2014. Eds. ‘Fandom and/as Labor,’ Transformative Works and Cultures, Volume 15. https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/issue/view/16

Stenger, Josh. 2006. ‘The Clothes Make the Fan: Fashion and Online Fandom When "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" Goes to eBay,’ Cinema Journal 45(4).

Totaro, Donato. 2011. “A Genealogy of Italian Popular Cinema: the Filoni,” Offscreen 15(11). https://offscreen.com/view/genealogy_filone

Lázaro-Reboll, Antonio. 2016. ‘Making Zines: Re-Reading European Trash Cinema,’ Film Studies 15(1), pp.30-53.

Wagstaff, Christopher. 1992. “A Forkful of Western: Industry, Audience and the Italian Western”. In Popular European Cinema, edited by Richard Dyer and Genette Vincendeau, pp.245-263. London: Routledge.

Wagstaff, Christopher. 1998. “Italian Genre Films in the World Market.” In Hollywood & Europe: Economics, Culture, National Identity 1945-95, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, and Stephen Ricci, pp74-86. BFI: London.

Endnotes

[1] http://www.trash.hr/?page_id=32

[2] https://www.thespec.com/whatson-story/6227862-welcome-to-trash-palace-a-connoisseur-s-collection-of-bad-movies/

[3] http://cfmu.ca/posts/126-so-bad-it-s-amazing-learn-about-hamilton-s-trash-cinema

[4] https://www.imdb.com/list/ls000042235/

______________________________________

William Proctor is Senior Lecturer in Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He has published widely on matters pertaining to popular culture, franchising and fandom, including comic books, film and TV. William is the co-editor of Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman for Routledge), Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch for University of Iowa Press), and the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna for Routledge). At present, William is completing his debut single-authored monograph Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for publication in 2019/20 (for Palgrave).