Cult Conversations: Interview with Craig Ian Mann (Part I)

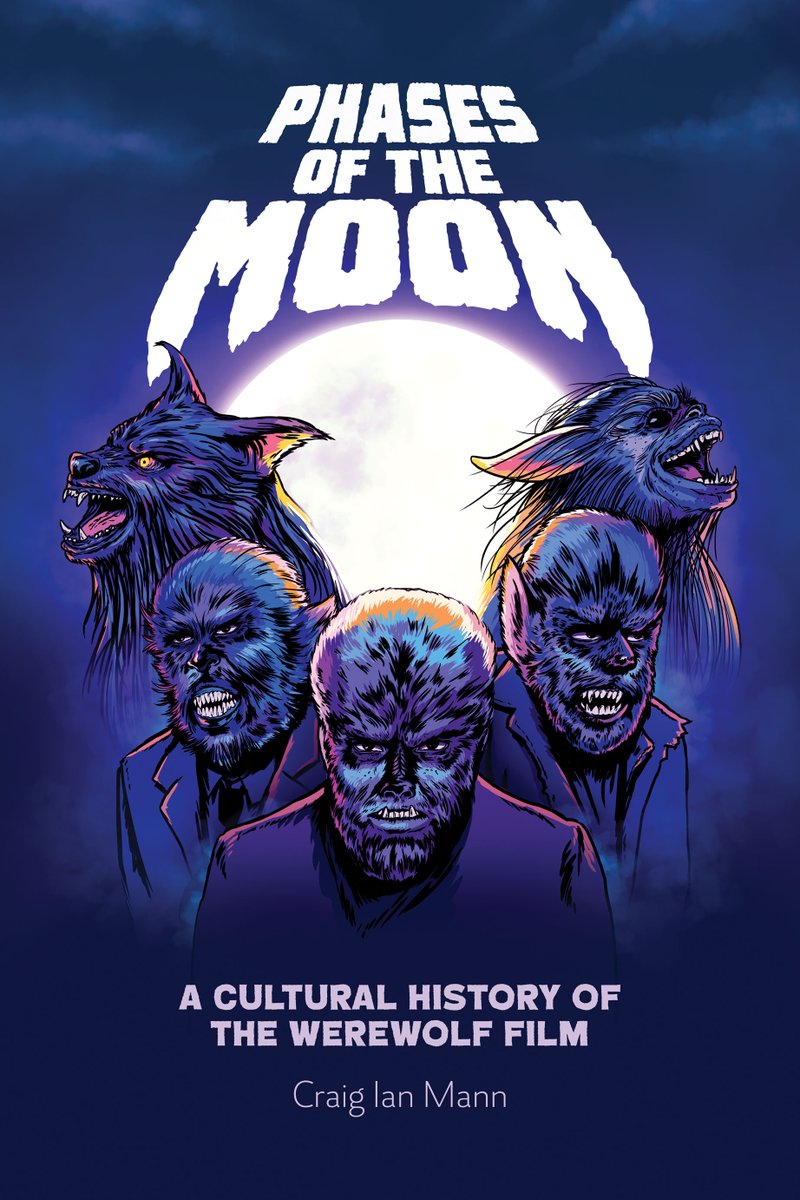

/Welcome to the final interview in the ‘Cult Conversations’ series. Last, but certainly not least, the following interview comes courtesy of Craig Ian Mann, whose PhD and forthcoming book centers on the figure of the werewolf in horror cinema. I have had a sneak peak at Craig’s thesis, and found myself reading the full document voraciously. Craig has a great deal to offer the academic landscape, and I’m certain his book will become widely read and, in time, seminal. In the following exchange, Craig and I discuss the origins of his research interests, and get into a debate about so-called ‘reflectionist’ readings of cinematic texts. In the meantime, look out for Craig’s Phases of the Moon: A Cultural History of the Werewolf Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

Your PhD and forthcoming monograph examines the figure of the werewolf in horror cinema. What sparked your interest in the topic? Did it begin with your own fandom? Or was it primarily an academic interest?

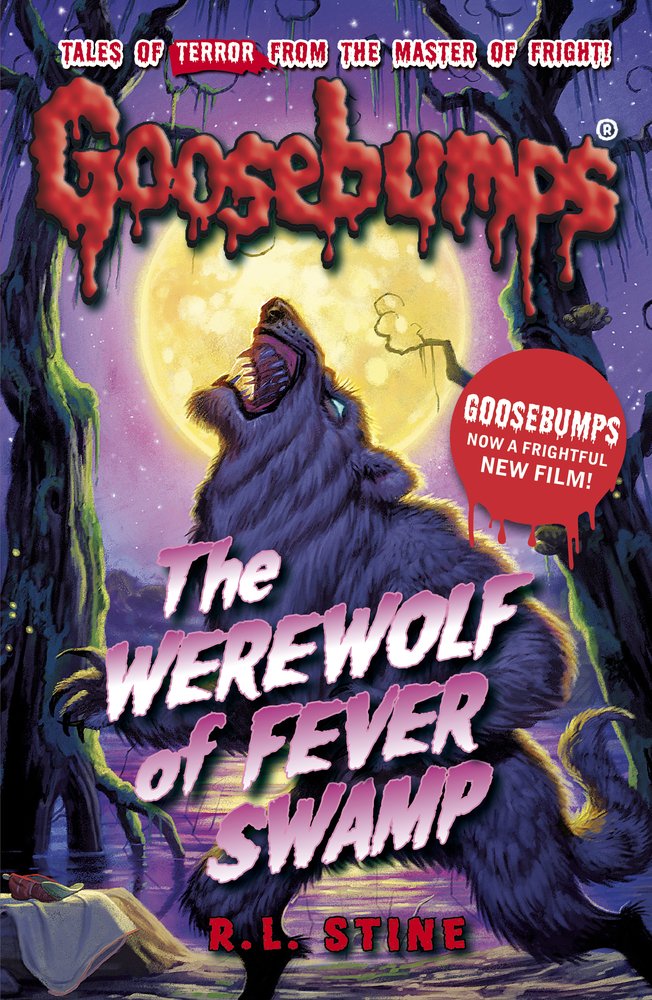

It definitely began with my own fandom. I have always been fascinated by monsters, but developed a particular soft spot for werewolves when I was young. The first werewolf film I ever saw was Wolf (1994), which I watched on VHS at a friend's house circa 1998 or 1999 – I can't remember exactly but something like that, anyway. I saw the first werewolf episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) at around the same time ("Phases", which I pay tribute to a little bit with the title of my forthcoming monograph, even if I ultimately couldn't find room for much discussion of werewolves on television). It was probably Wolf, "Phases" and R.L. Stine's The Werewolf of Fever Swamp (1993) that sparked my initial interest in werewolf narratives.

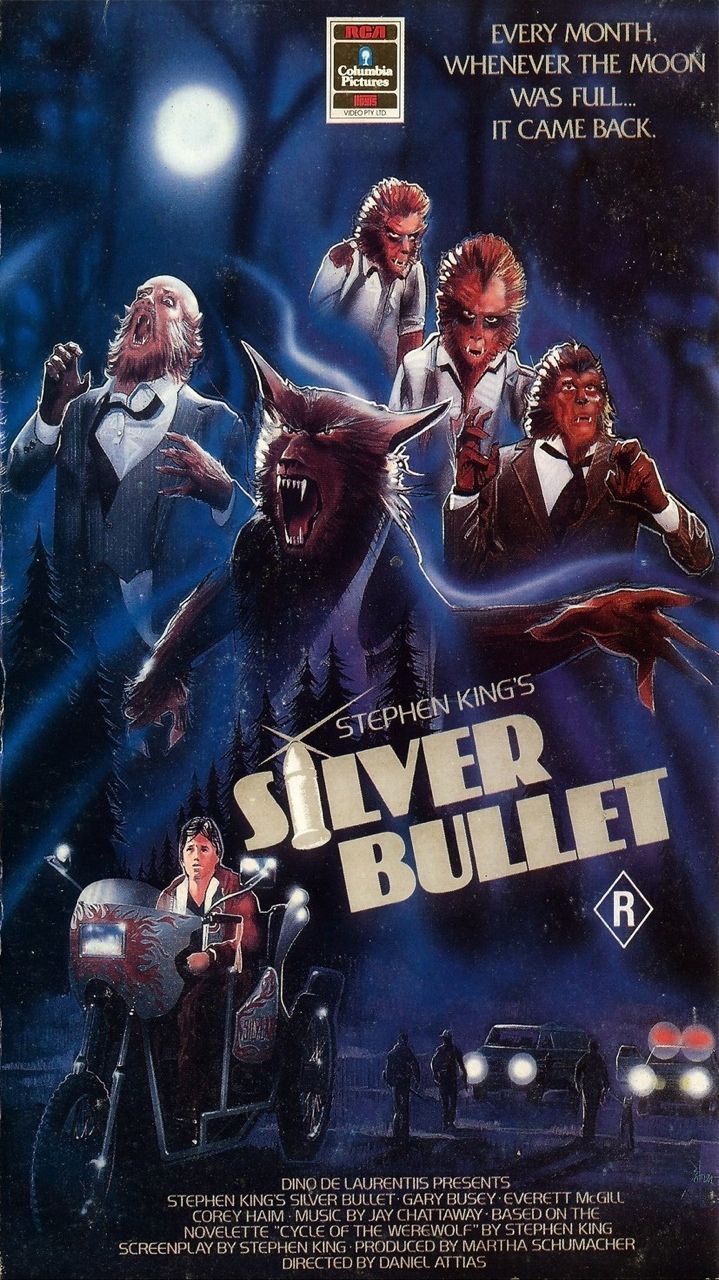

For better or worse I have an unshakable completist mentality (particularly in relation to cinema), so once I'd picked up that initial interest it was just a matter of consuming as much werewolf media as I could find. I think the next few werewolf movies I saw were probably The Howling (1981) and Silver Bullet (1985). I watched An American Werewolf in London (1981) for the first time on television a few years later and throughout my teens I either rented or bought everything from The Wolf Man (1941) to Dog Soldiers (2002) via Project: Metalbeast (or Metal Beast, 1995). I eventually caught up with the few classics I'd missed – most notably Werewolf of London (1935) – while I was an undergraduate. I'm still very much a fan now; WolfCop (2014), Howl (2015) and especially Late Phases (2014) are some favourites from recent years.

I first wrote about werewolf films while studying contemporary American horror at Sheffield Hallam University. The module leaned heavily towards cultural understandings of horror cinema as a site for working out real-world anxieties. I found it puzzling that so many monsters – vampires, zombies, Frankenstein's monster – had been the focus of entire books detailing their cultural histories, but there was very little work that approached werewolf media in this way. So I chose to write my undergraduate dissertation on the subject. I took a break and put werewolf films to one side for my master's degree, but came back to it for my doctoral studies and I'm now in the process of adapting the thesis into my first monograph. So it started with my fandom and developed into an academic pursuit.

How long have you been a fan of horror cinema? When did your journey begin and what kind of films precipitated your interest in genre films?

All my life, really – my taste has always leaned towards popular cinema. I vividly remember watching Westerns and science fiction at my grandparents' house when I was really young, so it was likely those early viewing experiences watching films like Winchester '73 (1950) and Forbidden Planet (1956) that shaped my interest in genre movies.

The first horror film I can remember seeing – when I was five or six years old – is Gremlins (1984). My pervading memory of the first time I saw it is Jerry Goldsmith's music. I watched it over and over again after that. It's probably the film I have seen the most times and remains one of my favourites – I still own the off-air VHS tape I first saw it on. In fact, I still watch it every Christmas Eve and have done without fail since I was a teenager (the film, not the VHS tape – I'm not actually sure if it would still play and I don't want to find out).

Putting werewolf movies to one side, other than Gremlins I can think of a few formative experiences in terms of shaping my interest in horror cinema. The first was not long after my parents first let me have a portable TV in my room. I'm not sure exactly when that was but I was definitely younger than eleven. I stayed up one Friday night and watched Candyman (1992). It scared me absolutely witless but somehow I stayed the distance. The sequel was playing on the same channel the next weekend and I tried to watch it, but ended up switching it off after five minutes.

After that, I have a very clear memory of renting Child's Play 2 (1990), and particularly the final scene in the toy factory. But I think the film that really got me hooked on horror was The Blair Witch Project (1999), which my sister bought not long after its video release. We watched it late one night when my parents were out, and it really got under my skin. I tend to return to it once a year or so and even as an adult it still unnerves me a little bit.

Can you talk more about the way in which the werewolf film expresses “cultural understandings of horror cinema as a site for working out real-world anxieties”? Do you see horror cinema as a ‘reflectionist’ vehicle for cultural and ideological phenomena? And if so, how would you respond to studies, such as Mark Bernard’s Selling the Splat Pack (2014), and Kevin Heffernan’s Ghouls, Gimmicks and Gold (2004), both of which argue that a reflectionist, aesthetic perspective fails to account for the economies of horror cinema—especially the way in which the reflectionist argument masks commercial impulses that aim to construct horror cinema as legitimately political, and therefore not the ‘bad’ object the genre is often framed in historical terms?

I wouldn't call myself a reflectionist, no, in that I don't believe horror cinema (or any kind of cinema) "reflects" the real world as such. And, of course, in recent years that particular term has been generally used by detractors rather than practitioners of cultural approaches. I don't think of films as reflections of a certain time and place, because that would suggest that they are somehow separate or removed from the society that produced them. I subscribe to the idea of cinema as a product of a particular cultural moment, i.e. that it is inextricable from the ideological debates, social norms and cultural shifts particular to the context in which it was produced and released. For me, all movies are political. Whether a film's politics are explicitly intended or not is another matter, and not one that is enormously important to me; the context in which a film is received is more interesting, and a wider culture may not share a filmmaker's values. That said, I think investigating authorial intent alongside textual analysis and a thorough account of the historical context surrounding a film can produce interesting results.

Of course, it would be absurd to suggest that any film has a single fixed meaning; a movie can mean different things to different people in different places and times. It may arise from a certain cultural moment, but by definition that means that not all viewers will receive it in that context – and while I think viewing any film is enriched by an understanding of its place in history, not all viewers will be armed with that knowledge, either. So it's important to make clear that my work explores the cultural significance of genre cinema specifically at the time of its creation and consumption. And even in a film's immediate context I'm interested in the possibility of a multiplicity of readings according to the experiences, values and orientations of different viewers. It isn't always possible to explore all the angles (for reasons of brevity as much as anything), but there are many films I study in the book – I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), to name an example – that are particularly thematically ambiguous, so I think about how those films can be approached from both sides of the political spectrum. And where there is evidence for it, authorial intent can add another interesting layer.

So, to tie all of those points together I'll take The Wolf Man as a representative example, for no other reason than because I've been thinking about it recently after discussing it on Twitter. The Wolf Man was written by Curt Siodmak, a Jewish writer and German ex-patriate who fled Nazi Germany to escape persecution, first to Britain and then to the United States in 1937. He found a career as a screenwriter and had his first big hit with The Wolf Man, the story of a British-American, Larry Talbot, who is bitten by a werewolf travelling with a group of gypsies during a trip to his ancestral home in Wales.

From Siodmak's side, this was very much a film informed by his experiences in Germany, and particularly the ways in which the country changed under Nazism. He was quite open about how his traumatic experiences seeped into his screenplays, and once said that there were "terrors in my life that might have found an outlet in writing horror stories." He was particularly interested in how the werewolf represented the transformation of a peaceful man into a murderer (just as Germany transformed from a republic into a fascist state). In fact, Siodmak had left Britain for America to remove himself even further from Hitler; his wife had convinced him to move to Hollywood because she had been terrified of an invasion. So the fact that Talbot is cursed by European forces that have metaphorically "invaded" Britain is also interesting.

This is not a reading that was likely to resonate in the United States at the time of the film's release, though. While there were certainly many German ex-patriots in the country at this time, the average American was unlikely to be able to empathise with a man who fled his home nation in fear for his life. But that's not to say that The Wolf Man wasn't received in the context of war. In fact, the film was released only five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and four days after the US declared war on the Empire of Japan, so it was very much tied to that cultural context. Before this point, the domestic experience of World War II had largely been the on-going debate between interventionists and non-interventionists. So in this sense, an American who is suddenly attacked by a foreign aggressor (in the form of the European gypsies who arrive in Britain and bring the werewolf's curse with them) is extremely relevant in that place and time.

David J. Skal argues that The Wolf Man and its three sequels – Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945) – parallel the American war effort, and there's certainly a case to be made that the sequels extend the original film's themes. After he is attacked on home soil, Talbot spends the next three films travelling to Visaria, Universal's fictional European country, and doing battle with all manner of irredeemably evil European monsters: Frankenstein's creature, Dracula, hunchbacks and various mad scientists with conspicuously Germanic names. So Talbot becomes analogous to an American soldier, forced to embrace violence and do awful things for the greater good – there's a real sense of personal sacrifice as a theme throughout all four of these films.

So The Wolf Man clearly meant one thing to Siodmak, something else when it was released to theatres shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and something else again when viewed alongside its own sequels, but in all cases it is important to consider its wartime context. It's interesting that even the famous poem can be interpreted either from the perspective of creator or consumer:

Even a man who is pure in heart

And says his prayers by night

May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms

And the autumn moon is bright.

The wording of the final line changed slightly in the sequels, but the poem remained basically the same. It's clear that the central message here is that even essentially "good" people can turn to violence in extraordinary circumstances, and that applies both to the German people embracing Nazism and the servicemen sent to fight the Axis forces once America had been drawn into war. That's just one example of how we can see the werewolf film as a site for exploring real-world anxieties.

So I hope that that answers your initial question. To say a little bit about the idea that cultural readings (rather than "reflectionist" readings) fail to account for the economics of horror cinema, I can certainly see that argument. Culturalists are generally more interested in thematic meaning and sociohistorical context than the circumstances of a film's production, and I don't necessarily see anything problematic in that – just as I don't see anything problematic in the fact that industrial approaches tend to put the film itself to one side. To find a form of holistic analysis that can account for everything is an impossible ideal. Single methodologies can't possibly offer a complete and definitive account of any movie, and mixed methodologies are likely to have shortcomings in attempting to cover all the angles. I'm also not an academic who quickly suggests that any particular framework should be considered entirely invalid or without merit. Though there are, of course, perspectives I prefer to take in my own work – and I certainly have my own scepticisms, too – there is always scope for scholars to take different approaches to the same material.

As for the idea that thinking about horror films in terms of culture, society and politics overlooks the fact that genre cinema is made to turn a profit, I find it interesting that this argument is most often levelled at culturalists who study horror. It seems odd to me that cultural readings of, say, science fiction cinema or the Western (two other popular genres that have also been historically driven by commercial imperatives) are widely accepted alongside industrial accounts – i.e. we generally buy that science fiction's visions of the future and the Western's reworkings of the past both tell us something about the present, despite the fact that they are both popular genres – but attempts to discuss the politics of horror films in this way are now more frequently challenged or disregarded. This has always seemed like a strange reverse-snobbery to me; are we so precious about horror's low-brow status that we must pretend it means nothing? Similarly, the idea that a film can be actively sold as subversive or oppositional does nothing to change the fact that the film itself can still be seen to be subversive or oppositional. I see no reason why studies of production, distribution and exhibition can't exist alongside analytical or text-based scholarship, and in fact the two can often complement and enrich each other. In short, it is possible for a film to be both a commercial product and a cultural artefact.

If I may be challenging, it seems that, on the one hand, you argue you “subscribe to the idea of cinema as a product of a particular cultural moment, i.e. that it is inextricable from the ideological debates, social norms and cultural shifts particular to the context in which it was produced and released,” but also competing interpretations may be available—and thus assuredly “extricable”. It seems that the former is a reflectionist stance—although I appreciate that detractors have adopted the term ‘reflectionist’ as a pejorative so I accept that “cultural reading” is more sufficient and less charged. If a film—let’s remain with The Wolf Man for a moment—is inextricable from its war-time context and that Siodmak’s authorial intention as you recount is a reflectionist perspective, as well as the notion that a democracy of interpretation exists that may operate outside of cultural, social and ideological contexts, I want to ask if you mean that films are inextricable from historically contingent contexts from a scholarly perspective? For if audiences can and do interpret films in a wide variety of ways, then it seems that they are indeed “extricable” at the point of reception. How would you respond to this?

For me, understanding the cultural context surrounding a film is of vital importance, hence my comment that film and history are "inextricable" in my eyes. But that's my view – of course films can be and often are extricated from that context and, as I've said, it would be plainly ridiculous to suggest otherwise. Films are read in many different ways by many different people. However, it is the work of a culturalist to make those initial historical circumstances clear and to interrogate how popular culture relates to them, i.e. to reintroduce context where it might otherwise be absent. So I am absolutely a believer in democracy of interpretation, but I also think any reading of a film is enormously enriched by an understanding of its place in history.

That doesn't mean, however, that films are to be taken as "mirrors," nor should they be considered to have any single, fixed meaning even in their immediate context. This is why I reject "reflectionism" as a term. When we discuss a film as a product of a cultural moment, we don't have to assign a definitive meaning to it. We can consider, per my comments on The Wolf Man, how a creator's values or interpretations may align with or differ from the larger culture that receives a film. Similarly, we can consider how different societal groups might read their own values into the same movie.

So I mentioned I Was a Teenage Werewolf briefly above. This is a film that has been the subject of a reasonable amount of academic attention in comparison to many other werewolf films. Most scholars agree that it is a product of a particular moment in American history – one that witnessed the rise of youth culture and a widespread moral panic surrounding juvenile delinquency. After all, it is about an adolescent who transforms into an animal. Even if we want to ignore its thematic content, it was sold by American International Pictures as a movie aimed squarely at the emerging teenage market (the trailer begins by addressing "teenage guys 'n' dolls").

Beyond an acknowledgement of that initial context, though, readings have varied wildly. In Seeing Is Believing (1983), Peter Biskind argues that it is an exceptionally conservative film that delivers a grave warning to teenagers: society will not tolerate delinquents. On the other hand, Mark Jancovich's reading in Rational Fears (1996) recentralises teenagers at the film's target audience, and suggests it is more accurately read as a film that expresses adolescent frustrations with an overbearingly conservative society. These readings are ideologically opposed, but they both relate directly to the film's historical context. And they are both equally valid; the film's narrative and aesthetics provide ample evidence to support either interpretation. So yes, context is enormously important to me and it is always a priority in my work – but I am interested in exploring multiple perspectives. I also recognise that alternative approaches will extricate films from their cultural moment entirely and go a different way. That's all part of academic debate.

Craig Ian Mann is an Associate Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at Sheffield Hallam University, where he was awarded his doctorate in 2016. His first monograph, Phases of the Moon: A Cultural History of the Werewolf Film, is forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. He is broadly interested in the cultural significance of popular genre cinema, including horror, science fiction, action and the Western. His work has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Popular Film and Television, Horror Studies and Science Fiction Film and Television as well as several edited collections. He is co-organiser of the Fear 2000 conference series on horror media in the twenty-first century.