Cult Conversations: Interview with Robin Means Coleman (Pt.I)

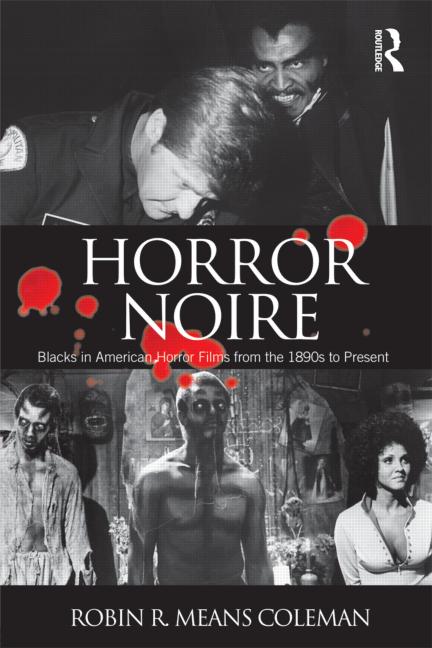

/With the release and enormous success of Jordan Peele’s Get Out in 2017, the politics of race has become a hot topic—and rightly so! It is with this in mind that Professor Robin Means Coleman’s Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to the Present came highly recommended—by David Church, no less. I cannot urge interested scholars to seek out this monograph enough, be in in the field of horror studies, critical race theory, sociology, or film and media studies more generally. Professor Coleman has had quite the eclectic career, writing on Black comedy, Spike Lee, and African American audiences, among other subjects, for the best part of two decades at this point. In the following interview, Professor Coleman and I delve into her own aca-fandom and the politics of the horror genre. But firstly, make sure you head off to your digital shopping mall to pick up Horror Noire! I guarantee you won’t be disappointed.

Also, Robin has a new documentary film, also called Horror Noire, coming to Shudder worldwide on February 7th 2019. During the first week of February, there will be a Hollywood premiere event with the following guests: "Discussion following with Ashlee Blackwell (co-writer/producer), Xavier Burgin (director), Tananarive Due (executive producer), Tony Todd (actor, CANDYMAN), William Crain (director, BLACULA), Ken Foree (actor, DAWN OF THE DEAD), Keith David (actor, THE THING). Moderated by Lisa Bolekaja."

Check out the trailer here.

—-William Proctor

Would you identify as a fan of the horror genre in general terms?

In 1998, I published my first book, African American Views and the Black Situation Comedy: Situating Racial Humor, which did not just focus on situation comedies, but on Black situation comedies. In 2011, I published my fourth book, Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, which did not just focus on horror films, but on Black horror films. Fandom certainly brings me to the genres that I study. However, I give these genres precious attention because I believe they are important—a move of scholarly activism—to recuperate these purported ‘bad’ objects that set its sights on Blackness, and do so in an entertaining way. I want to remind scholars that the Black sitcom Roc (1991-1994) is just as socio-politically insightful as All in the Family (1971-1979). I want to remind scholars that the Black horror film Def by Temptation (1990) is just as gleefully spooky, wrapped up in a ‘how are we living our lives’ message, as A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). In my work, I give prominence to Blackness because naming a thing need not be bad, and invisibility of history, culture, and experience gets us nowhere. It also helps a great deal that I am more than a fan; I am someone who truly respects (and can ably engage in critique of) genres like Black horror.

Did your journey into horror begin as a fan or as an academic?

Fandom came first. The academic focus followed.

I happily lay my interest in horror and science fiction at the feet of Bill ‘Chilly Billy” Cardille. William Robert Cardille (1928-2016) was born, raised, and worked as a TV and radio broadcaster in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I, too, was born and raised in Pittsburgh, and I grew up on a healthy diet of Bill Cardille’s programming—I remember him as our weather announcer and for three decades he was a host on the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Labor Day Telethon. He started at WIIC-TV (Channel 11) in Pittsburgh in 1957, more than ten year before I was born. In 1964, he began hosting his most popular program Chiller Theater, and was dubbed “Chilly Billy.” Late on Saturday nights, around 11:30pm, Chilly Billy would come on and show a double or even a triple feature—something like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), followed by Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) or Bride of Frankenstein (1935), A Study in Terror (1965), and The Raven (1935). I would ask my mother to fry up a batch of chicken livers and bake a chocolate cake—hey, this is what I liked as kid!—and we would lay across her bed, eat cake and livers, and watch Chiller Theater until I could no longer keep my eyes open.

Today, reflecting back, I have come to understand two things about that experience. First, I really liked Chilly Billy’s style of hosting Chiller Theater. He was himself. He did not dress up in some vampire costume and make-up to host the show. He wore a suit and tie, just as he did when delivering the news or weather. He was himself, affable and informed. That brought a respectability to the genre that I know now deeply influenced me. Second, it informed my taste in the kind of horror that I like to watch and study. Chiller Theater goes off the air on New Year’s Eve in 1983 just as slasher and torture porn horror is really taking hold. The 1980s was the era of “video nasties,” as they were called in the UK. I could not imagine the homey Bill Cardille bringing these particular kinds of movies to audiences on broadcast television. Black horror movies, for the most part, are not wall-to-wall splatter. They are story-driven and sociopolitically-driven, like a Get Out (2017). They typically are not propelled by gore. I love studying those kinds of narratives; I guess that is the Chilly Billy in me.

I often tell people that writing about Black horror began as a sort of birth right. As I said, I was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which was also home to George Night of the Living Dead Romero. That is pretty cool—Bill Cardille and George Romero! Romero filmed the seminal, now cult classic zombie horror film Night of the Living Dead (1968) around the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, and even featured local Pittsburgh personalities in the film. So, here is the connection: George Romero casts Bill Cardille to do a cameo as himself, a reporter, in Night of the Living Dead. Cardille shows up on set in his WIIC-TV station wagon. More, since Romero shot Night in real communities, using real locals, they came out to see Cardille; they recognize him. In the movie, Cardille does a real interview about a fiction. He very seriously interviews a Sheriff McClelland, played by an actor, about the rising zombies, “Chief, if I were surrounded by eight or ten of these things, would I stand a chance?”

Later in my life, when I would go shopping in the Pittsburgh-area shopping mall, Monroeville Mall (or ‘the Mall’ as we called it back in the day), I was keenly aware that I was quite literally walking in the footsteps of George Romero. The Mall was the mundane-turned-terrifying claustrophobic centrepiece of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1979).

In Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from 1890s to the Present, you argue: “the boundary-pushing genre of the horror film has always been a site for provocative explorations of race in American popular culture.” Historically, the horror genre has often been critically excoriated for reactionary politics, while in recent years there has seemed to be a shift. Given the broad reach of your book in historical terms, what have you found out about these “provocative explorations”? How might you describe Horror Noire for readers unfamiliar with your work?

Actually, I did not know that the horror genre has been excoriated for reactionary politics! In fact, I am not entirely sure what this means. Is the claim that horror throws us into some kind of horrid cycle where some good thing happens, but the genre reacts in a way that is so contrary that it impedes true progress of that good thing? And, this view is reserved for the horror genre? That’s a no for me dawg.

My view of the genre is absolutely the opposite: as one of the most innovative, unrestricted genres it is able to be brave and take the most perilous risks in exploring social, cultural, political, and identity topics. It challenges the status quo, exposes the limits of normativity, and makes us question our blind investment in concepts that we accept as common sense.

Let me be clear about horror being an “unrestricted genre.” Horror is not bound by some respectability expectations. Horror movies are not released during Oscar season in the hope they will garner the approval and acclaim of critics. They are not Oscar bait films like those period dramas put out by the Weinstein Company like The Kings Speech (2010), The Butler (2013), or The Imitation Game (2014). My point, horror is free. It is liberated from the confines of being an “epic.” Though, sometimes horror sheds its B-movie stereotype to capture the imagination of the industry—think The Silence of the Lambs (1991) or The Exorcist (1973).

The horror genre is daring pedagogy. It is like a syllabus of our social world. You want a complex study in racism and location (urban vs suburban), watch Get Out (2017). You want to interrogate police brutality, the carceral state, and a person’s breaking point, watch Soul Vengeance (1975). You want morality tales, check out The Blood of Jesus (1941). Dawn of the Dead (1978) provides critiques of conspicuous consumption. Scream, Blacula, Scream (1973) rejects the stereotypical portrayals of voo doo.

This does not mean that horror always gets things right. The tightly scripted morality tale Def by Temptation (1990) has so much going for it, but it is deeply problematic in its treatment of queer identities. JD’s Revenge (1976) also presents a high quality script, but propagates domestic violence.

I do not see provocative explorations as a recent phenomenon; rather, I see this in horror’s very DNA. One simply has to see it. For example, when, in 1896, George Méliès conjures up demons, skeletons, ghosts, and witches before they are vanquished in the shadow of a crucifix in his short film “Le Manoir du Diable” (“The Haunted Castle”), Méliès is not simply entertaining us, he is challenging us to come to terms with the intersections of our imagination and Judeo-Christian belief systems.

Professor Robin R. Means Coleman is Vice President and Associate Provost for Diversity and a Professor in the Department of Communication at Texas A&M University. A nationally prominent and award-winning professor of communication and African American studies, Prof. Coleman’s scholarship focuses on media studies and the cultural politics of Blackness. She is the author of Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (2011, Routledge) and African-American Viewers and the Black Situation Comedy: Situating Racial Humor (2000, Routledge). Prof. Coleman is co-author of Intercultural Communication for Everyday Life (2014, Wiley-Blackwell), the editor of Say It Loud! African American Audiences, Media, and Identity (2002, Routledge), and co-editor of Fight the Power! The Spike Lee Reader (2008, Peter Lang). She is also the author of a number of other academic and popular publications. Her research and commentary has been featured in a variety of international and national media outlets. Prof. Coleman’s current research focuses on the NAACP’s participation in media activism.