Cult Conversations: Interview with Shellie McMundro (Part II)

/Let’s return to this notion of cultural trauma. I agree that films are “a product of the time in which they were made,” at least to some extent—refraction not reflection, however—and that tracking and charting the found footage subgenre, both diachronically and synchronically, can teach us important lessons about the shifting lens of what constructs the ‘real.’ Could you expand on the cultural trauma aspects of The Blair Witch Project in comparison to Quarantine and perhaps the social media horror, Unfriended? As each film was produced in almost ten-year intervals, what can this tell us about the texts comparatively from a cultural trauma perspective?

I’m in no way saying that every found footage horror film somehow links to cultural trauma, but the subgenre is a really interesting and fertile ground for representations of trauma – especially in our ‘tape everything’ culture.

The element of The Blair Witch Project that I admire the most is just how oppositional it felt compared to other horror films of the late 1990s. Part of its effectiveness, I feel, is that we were so used to very glossy productions full of beautiful people getting killed off one by one, I’m thinking here of Scream, Urban Legend, and the like, where it was a given that at some point someone had to cleverly announce ‘It’s like were in a scary movie…’. The Blair Witch Project to me really felt like a visceral reaction against that kind of self-aware post-modern horror film. It is still a self-aware film, but with zero irony. Its effectiveness comes from the film very much returning to basics on the cultural anxiety front. You have, in The Blair Witch Project, a folk tale about a folk tale, in a way. There is the myth of the witch established up front, with the interviews from townspeople and Heather’s exposition, which was supported by the plethora of paratexts surrounding the film, and then the narrative uses that base cautionary tale to launch its own folk tale about the dangers of going into the woods that we have seen in Hansel and Gretel and Red Riding Hood, going back to this primal fear of being lost in the woods. A quote from the film that stays with me is when the trio begin to realise that they are hopelessly lost, and Heather says something like ‘It’s very hard to get lost in America these days, and it’s even harder to stay lost’. Then, later in the film, the group are talking about their situation and Heather argues that everything that is happening can’t actually be possible because ’This is America. We’ve used up all our natural resources’. There is something to be said of the film presenting this anxiety about America, being American, and the position of America on the brink of the new millennium. There is this resonance with the American frontier, and this overconfidence that at the brink of the millennium we have won against nature, we have beaten back this hostile force and have emerged victorious, but the film reminds us that there are still hostile places in America, places we cannot master.

Moving onto Quarantine, this film is a really interesting case study, not only because it’s a great film, but because it’s also a remake of a great film! Quarantine is a remake of the Spanish horror film Rec, which only came out a year before it in 2007. It sticks pretty close to the original film, apart from the ending, which a lot of audiences didn’t like. In Rec we find out that the cause of a rapid spreading infection is of religious origin, whereas in Quarantine it is a doomsday cult that have developed the virus. It is reductive to say ‘all American horror films made post 9/11 are about 9/11’, and in a few years time I think we might see that replaced with the sentiment that ‘all American horror films made post 2016 are about the Trump presidency’. However, I can’t personally get away from the fact that in Quarantine, and in Rec, you have these images of reporters with cameras, firemen, and policemen, stuck in this tall building and they can’t get out. There is a definite factor there of what Adam Lowenstein calls ‘the allegorical moment’ in relation to 9/11.

Unfriended is a great film, and I was so excited to see how they built on it for Unfriended 2: Dark Web. What Unfriended did is really herald the emergence of a sub-sub genre within found footage horror, there are a lot of different terms for it, but I use ‘social media horror’. An abundance of films came out in the wake of Unfriended like SickHouse, which used apps like Snapchat as a horror format, and they work surprisingly well. Unfriended is especially affective if you watch it on a laptop, it’s an uncanny experience, and the first time I watched it, I got so involved that I instinctively tried to move the mouse pointer back when the character moved it! In terms of cultural anxieties, Unfriended uses what Jeffrey Sconce has termed as ‘haunted media’ – which he tracks back to telegraphy – to engage with themes like identity theft, cyberstalking, and cyberbullying. There is a thread that runs through the film which relates to the lifespan of the internet, or more, how long things remain on the internet once you have put them out there on the web. We have seen recently, for example with the controversy over tweets from James Gunn, how the internet has a long memory, and can come back around to haunt you. To be honest, tracking found footage horror over the last twenty years has been fascinating, because the anxieties emerging in Unfriended weren’t even on anyone’s radar back when The Blair Witch Project was released.

There is a tendency in scholarly circles to analyse cultural objects as if they are reflections of the socio-political and cultural era in which they were produced and that historical context can be simply read off of the text. In Selling the Splat Pack, Mark Bernard deftly critiques this idea, arguing that (so-called) ‘reflectionist’ approaches “is a quandary that affects all film studies” (2015: 31). In Bernard’s account, the idea of horror-as-reflection is a discourse that has been used by producers to authenticate the genre and imbue it with an aura that operates to circumnavigate its broader cultural low-status. Says Bernard:

“The genre has also inherited the tendency to be read as producing allegories of the anxieties and traumas of its particular historical moment without due consideration given to the industrial and technological factors that play a role in what types of films are produced, distributed and widely seen by audiences. If course, this interpretative strategy is not unique to horror film” (2015: 31).

How might you respond to Mark Bernard’s criticism of ‘reflectionist’ approaches here?

I’m not a fan of the term “reflectionist”, I certainly wouldn’t position myself as someone who does “reflectionist” readings, as I don’t think that any cinema “reflects” the context in which it is made but is more a product of it. This is true of anything that comes out of a cultural moment, whether it be cinema, television, music, art, or slang. With my own research, I’m attempting to use cultural trauma as a framework, but am underpinning my findings with reviews and articles on the films from their release period, and with newer films, looking at the response to them on social media – how these films were/are talked about by fans, non-fans, academics, and aca-fans. The reason I’m supporting my analysis of the films with other evidence, is because I’m always aware that textual readings only tell us what one person thinks, and might not be what everyone who watched the film thought or got from it. I would argue however that if we get stuck in purely looking at industrial and technological factors, we just end up repeating facts and figures. However, if we put both together – or at least try to assimilate the two approaches – it would be far more fruitful.

I would also say that as with all approaches to cinema, no one approach covers everything. For example, a psychoanalytic reading of a film may miss something that a formalist reading would pick up and vice versa, it’s impossible for one method to do it all. For me personally, cultural studies and trauma studies was always the way I was going to go because of my background in history, but I’m completely open to other methodologies and expect I will adapt and engage with new approaches as I continue in my research career.

I find the idea that the horror genre specifically somehow has to be authenticated or legitimised – and that a way of doing this is through cultural readings – very odd. Although I started this project because I felt like found footage horror was unfairly perceived as a “low” form of horror, I don’t personally feel that the wider horror genre has to be legitimised scholarly, as we have already achieved that to a certain extent. Although, there certainly is still a strange hierarchy of horror both in horror fandom and horror scholarship. In summary, I would argue that with all methodologies, there will be an element that is not covered, but that doesn’t necessary make them a poor method to use.

Could you expound on your comment about “a strange hierarchy of horror both in horror fandom and horror scholarship.” What is this strange hierarchy and how do you view its operations both in fannish and scholarly contexts?

The study of horror cinema is definitely a field that has hard won its legitimacy, but seems to have retained this supposed stigma of being ‘low brow’. We can see this at work periodically, each time a horror film or a group of horror films are released and critics absolutely refuse to let them sit comfortably within the classification of ‘horror’. Most recently, we have seen it with the term ‘elevated horror’/’post-horror’ that has been used to describe films such as Hereditary, A Quiet Place, and It Comes at Night. To me, the term ‘elevated horror’ is such a backhanded compliment, it is really the carving out of a little niche that could be re-termed as ‘horror I personally enjoy’, as opposed to ‘horror that I think is trashy and ‘horror fans’ might enjoy’. I find it bizarre, and – I might be wrong in this – but you don’t really see this to the same extent in other cinematic genres, you don’t have ‘elevated drama’ for example.

In terms of scholarship, the horror genre is often positioned as being in a state of crisis, most often in reference to the multitude of remakes that were released in the mid 2000s. But we only need to look at the sheer volume of cinematic and televisual horror products in the last few years to see that is absolutely untrue. I read a journalistic article on last years IT recently, that posited that the film was ‘bad news for horror fans’. I thought that was interesting – why would IT be bad news for horror fans? – It seems to come down to this idea that horror fans are troubled somehow by horror being a successful genre. I’m not a fan studies scholar, so am unable to delve into how much truth is in that statement, but I can comment on my own possible bias as a fan of horror.

In my work, I look into the response on social media to found footage horror films, and I’m reminded often of Mark Jancovich’s comments on horror fan response to the success of Scream. He argues that no one seemed troubled by how successful the film was apart from horror scholars and fans, going to on note that the response online was ‘guarded and even out right hostile’ (2000: 475). In turn, I admit that I am guilty of this myself at times, I have always been protective to a certain extent over the horror genre and its perceived status as an oppositional genre. For example, when I first started my research, I was vitriolic in my dislike of the Paranormal Activity films, and made a conscious effort to step back and address my own position on that series of films. I delved into how much of my distain for the series came from how I perceived their actual narrative and aesthetic qualities, and alternatively questioned whether it was the fact that they were so successful and therefore to my thinking, not “proper” horror that made me dislike them. I have endeavoured to avoid making judgements of “value” in regards to the found footage subgenre in my research.

I have found a great deal of scholarly work holds contemporary horror up to a benchmark of 1970s horror cinema. For example, Reynold Humphries noted that ‘we shall see no more films of the calibre of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ (2002: 195). While it is undeniable that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is an absolute classic of horror cinema – it’s brutal, it’s unrelenting, it’s amazingly shot, and has a fantastic score – I wouldn’t hesitate to place The Blair Witch Project in the same sentence as it, as it is also a horror genre classic, but this may seem like sacrilege to some! Matt Hills made a great point when he looked at horror scholarship and asked why some films were ‘canonically recuperated’ while others were not (2012: 111), and this is something I have attempted to address. It is something of a privilege, as a film scholar, to be in a position where you might be able to bring lesser-known films to wider attention, and there is definitely a shift in horror scholarship that seeks to redress the imbalance caused by so much focus being given to a relatively small pool of horror directors and movements. Overall, in our current age, with the internet and social media, there is far less opportunity for cultural gatekeepers to step in and tell us what we all “should” be watching – not just in horror cinema, but across all forms of popular culture – and this can only be a good thing!

And finally, what five films would you recommend that you feel represents ‘the best’ that found footage cinema can offer and why?

A lot of your questions have been tough to answer, but this is the toughest! I’ve missed out some great examples of the subgenre, but I didn’t want to go for anything really obscure or hard to get hold of, instead I have chosen films that I feel hit the key moments of the evolution of found footage horror cinema.

The Blair Witch Project (Eduardo and Sanchez, 1999)

This one was a bit of a given, and I apologise for being thoroughly predictable! This film follows the story of three student filmmakers who want to make a documentary about a local legend – The Blair Witch. They enter the Burkittsville woods in Maryland and are never seen again. The film we watch is presented as the footage they captured before their disappearance, which was recovered from the woods. There is so much fascinating work available on this film, and the main reason for this is that The Blair Witch Project is – almost 20 years after its release – still such a compelling film. Made for so little money, it is a masterclass in constructing fear around suggestion. I would highly recommend searching out the accompanying documentary, The Curse of The Blair Witch, and watching that beforehand.

The Bay (Levinson, 2012)

The Bay really shows how diverse the found footage horror format can be. Released in 2012 – post YouTube and iPhones – the film uses a variety of different types of footage (dashboard camera, handheld cameras, FaceTime messaging, Skype and webcams to name only a few), to present a narrative about a governmental cover-up of water toxicity in a small town on the Eastern shore, which has created mutant isopods (which are far more creepy than they sound!). There is a prevalent theme in the found footage horror subgenre of characters searching for truth or evidence, of media mistrust, and of the general public being in danger of becoming collateral damage. You can definitely see these themes in The Bay, as well as in Rec/Quarantine, Diary of the Dead, and many others.

Quarantine (Dowdle, 2008)

You may wonder why I have chosen Quarantine here and not Rec, and my reasoning for that purely comes down to personal preference, Rec could just as easily be on this list. Either film would make for a great comparison viewing with The Blair Witch Project – both films use the same basic found footage format as The Blair Witch Project, but in terms of energy and visceral impact, take that form careening off in a massively different direction. Quarantine’s main character, Angela, is a television reporter who – along with her cameraman Scott – is documenting a nightshift with the local Fire department. They are attending what seems to be an odd but ultimately low risk call, when all hell breaks loose and they find themselves trapped within a quarantined zone. The reason I have selected this film is because of how quickly it descends into high octane chaos – a common complaint about found footage horror is the amount of dead time viewers have to sit through – this film wastes no time in placing the camera in the middle of panicked action sequences. I have a lot of favourite parts in this film, and overall it shows how the often maligned shaky, unsteady framing of found footage horror works so well within a high energy film – it adds to the atmosphere of dread and frenzy so well.

The Sacrament (West, 2012)

Years after watching it for the first time, I still can’t get over The Sacrament. I’m a huge fan of Ti West, and what he has created here is just superb. The Sacrament is a modern reimagining of The Jonestown Massacre of 1978. By featuring the real life media brand Vice, and their specific style of immersionist journalism, West presents to us an interpretation of what happened just before and during the Jonestown event. It’s an unflinching film at times, and has a level of emotional impact that still knocks me sideways each time I watch it. It’s an interesting film within the subgenre as well because it actually looks so good – if you watch this film after something like The Last Horror Movie for example, it looks so crisp and slick – with barely any shaky handheld moments that the subgenre at this point had become known for. This doesn’t detract from the film, far from it, it makes sense as the characters in the film aren’t a bunch of amateurs with camcorders, but professional journalists caught up in a newsworthy event.

Marble Hornets (DeLage and Wagner, 2009 – 2014)

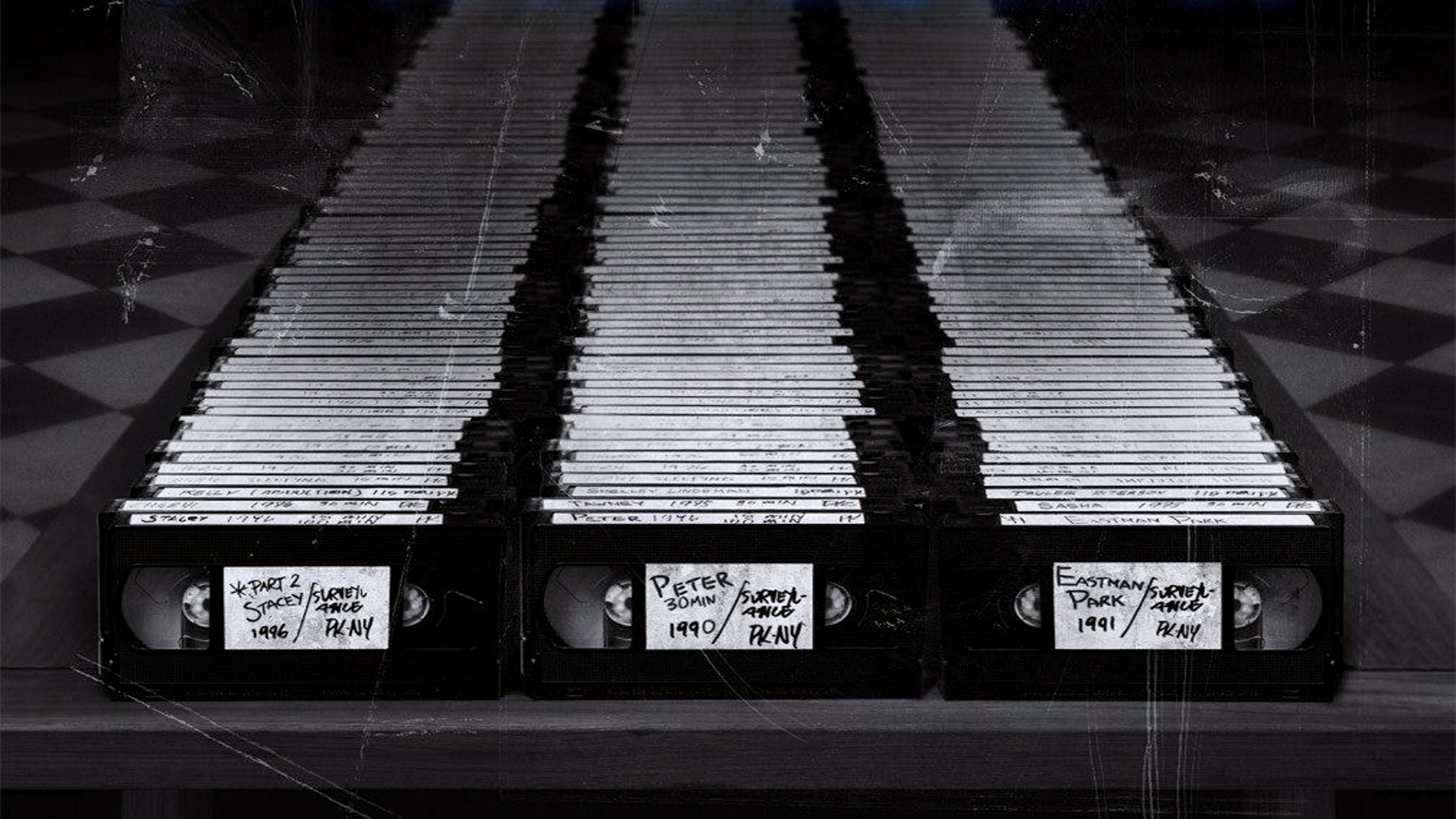

So this might be cheating a little, but Marble Hornets is a YouTube series which initially details a young man, Jay, looking through raw footage of an abandoned student film given to him by a friend, Alex, the film’s creator. Alex has forbidden Jay from ever trying to discuss the tapes with him. As you can imagine, the footage starts to become fractured, odd, distorted, and ever more creepy as the story progresses. I started watching Marble Hornets around 2011, and was instantly enthralled by it. Along with the YouTube entries, there were also Twitter accounts that tied into the storyline, and a side channel on YouTube, totheark, that also released videos that fed into the storyline. I don’t want to go too far into the background of this series, but it grew out of the Something Awful forum post that birthed Slenderman, and is the best Slenderman media product I’ve seen by a long way. I love how the flexibility of an online horror story like Slenderman enabled the creators of Marble Hornet’s to run with an idea and make a completely chilling and complex online narrative, watching it at the time when the entries were being released just made me as an audience member feel so involved with the story. A lot of copycat narratives have followed in the wake of Marble Hornets, none as brilliant, so I would wholeheartedly recommend giving the series a watch.

Shellie McMundro is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Roehampton, where she is examining found footage horror cinema and its connection to cultural trauma. She has presented her work, on found footage horror and additionally on new media horror, period drama, and horror gaming, at a variety of conferences. Shellie has a forthcoming article in the European Journal of American Culture, which ties together research on American Horror Story, The True Crime fandom and school shooters. Her research interests are extreme horror, new media, trauma theory, online fandoms, and transmedial texts.