Cult Conversations: A Series on Horror, Exploitation and the Gothic

/An Introduction and a Provocation

By William Proctor

Over the past year or so, horror cinema has been discursively underpinned by what entertainment critics have described as a “new golden age,” a “renaissance” that is demonstrative of an unequivocal cultural, industrial and attitudinal shift. As SyFy’s Tres Dean claims,

The past five years or so have seen the release of such a wide array of genre-defining horror films that it may be time to go ahead and call a spade a spade: We’re experiencing a genuine horror renaissance.

Likewise, Daily Beast’s Jen Yamato argues that

The mainstream horror movie is, sadly, the last place anyone who’s ever seen a mainstream horror movie would credibly look for critical acclaim—not that horrorhounds wouldn’t love to see an impeccably crafted four-quadrant slasher sweep the Oscars.

According to Michael Rothman for Consequences of Sound, “horror isn’t just having a resurgence, it’s taking over.”

Writing for the BBC, Nicolas Barker claims that, in historic terms, horror has traditionally been the black sheep of the Hollywood genre system,

a slightly embarrassing, bargain-basement alterative to mainstream drama […] You can understand why [horror films] might not appeal to a producer with an Oscar- or BAFTA-shaped space in their trophy cabinet.

Some critics argue that this so-called “new Golden Age” is best exemplified by the rise of Blumhouse productions, with Jason Blum’s ‘cheap and nasty’ economic model outperforming blockbuster franchises and films, at least as far as return-on-investment (ROI) goes. The Oscar nod for Jordan Peele’s Get Out is, of course, most often heralded as ‘proof’ that horror is transitioning out of the cult ghetto and into mainstream prominence. “For the first time ever,” exclaims Scott Meslow for GQ, “the most critically lauded movie released [in 2017] is a horror movie.” Blumhouse has “cornered the market on inventive horror,” argues Tracy Palmer.

Writing for The Guardian in September 2017, Anna Smith asked:

So how did these once fringe-films move into the heart of the mainstream?

Smith’s question, perhaps a rhetorical flourish more than anything substantive, suggests that the terms ‘mainstream’ and ‘horror’ are not easy bedfellows, setting up a binary between popularity and fringe (or the incredibly amorphous term, ‘cult’). The second decade of the new millennium is, as many critics have pointed out, a high generic watermark represented by ‘quality horror,’ ‘smart horror,’ ‘high concept horror,’ ‘elevated horror,’ ‘horror-adjacent,’ and ‘post-horror,’ terms that, in Nicolas Barker’s account, operate as “back-handed compliments,” bolstering the notion that the genre is much maligned.

But has it not always been the case that horror cinema has been historically less a coherent category than, as with all genres, a system of currents, cycles and trends that have pumped valuable oxygen and blood into “the heart of the mainstream” for almost a century? For if Hollywood “has always relied on horror movies,” then the suggestion that the genre has recently been elevated from the margins and thrust into the spotlight is little more than discursive ballyhoo, I would argue. Indeed, the suggestion that contemporaneous horror media is somehow indicative of a widespread ‘renaissance’ would mean that there has been a fallow period from which the genre has risen into prominence once more.

But has horror ever really gone away? Is the genre truly a niche or cult object? And would it be at all accurate to claim that horror cinema has historically been categorically despised and maligned?

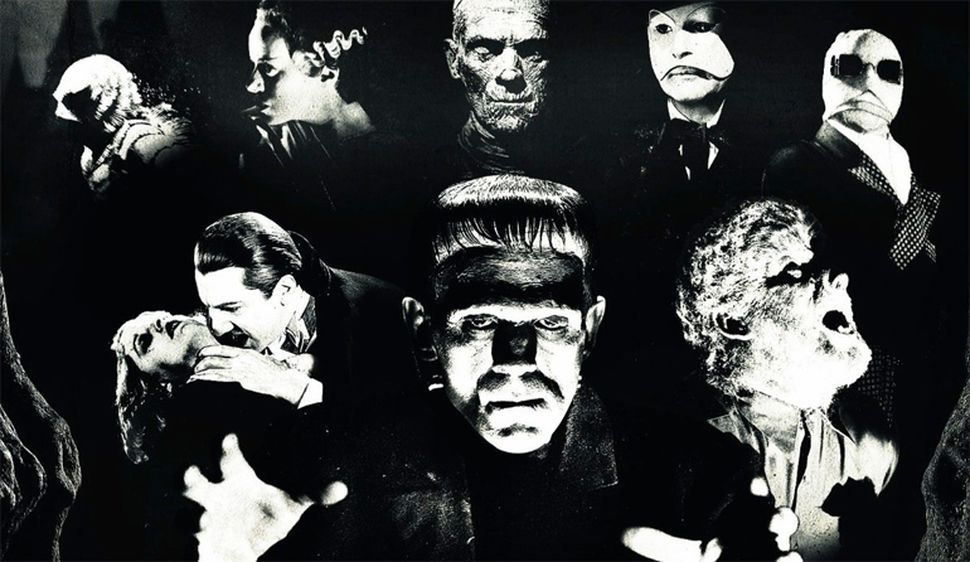

In cinematic terms, the genre has inarguably been a key organ in “the heart of the mainstream” since the turn of the twentieth century. Prior to the coming of sound, entrepreneur and pioneer, Thomas Edison, produced the first film adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1910, drawing on the gothic tradition at a time when the horror genre was in utero. Lon Chaney, “the man with a thousand faces,” was perhaps the first star of (proto) horror cinema, most famously playing lead roles in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1923), and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), the former of which was Universal’s “super jewel,” the most successful mainstream picture for the studio at that point. With the inception of sound in the early 1930s, Universal’s Carl Lemmle Jnr continued to green-light adaptations of gothic literature, leading into what has been termed the first Golden Age of horror films usually illustrated by the seminal ‘Universal Monster’ cycle. In 1931, Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein shattered box offices across North America, resulting in horror sequels and series swiftly becoming a major cash nexus of the Hollywood motion picture industry.

During the period, it was not only Universal that tapped into audiences’ appetite for blood-curdling cinema, but other studios produced a welter of horror pictures as well. Alison Peirse aims to redress this gap in After Dracula: The 1930s Horror Film, emphasizing “the diversity of horror film production during the 1930s”:

Many of the films that appeared over the next few years [after Dracula] diverged quite significantly from the mechanics of Universal’s gothic vampire story. The Gaumont-British film The Clairvoyant (1933) is grounded in spiritualism and British popular culture; Murders in the Zoo (1933) is a story of lip-sewing sadism and murder set amongst real-life big cats and snakes; while The Black Cat (1935) is an occult shrine to modernist architecture and design.

Paramount also boarded the horror bandwagon in 1931, producing Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, featuring Fredric March as the eponymous split personality, a performance deemed so incredible that March walked away with the Best Actor in a Leading Role Oscar at the fourth annual awards, as well as Most Favourite Actor at the Venice Film Festival.

And while classic horror films might well seem excessively camp or outmoded to audiences today—my own undergraduates tend to laugh at Whale’s Frankenstein, for instance—the emergence of horror pictures during the transition from silent cinema to “talkies” attracted the ire of censors and moral campaigners. As recounted by Peirse, an administrator of the Production Code asked of Hays: “is this the beginning of a cycle that ought to be retarded or killed?” It was thus not the attack on The Exorcist in the 1970s, or the so-called “video nasties” in the 1980s that first put horror cinema in the dock.

Between 1931 and 1936, horror cinema remained at the epicentre of Universal studios’ output, so much so that the decision to cease producing horror pictures in order to address criticisms of the conservative moral brigade, as well as implementation of the production code and the introduction of the H-Rating in the United Kingdom— H standing for horror—ended up leaving Universal on the cusp of bankruptcy. It was only by returning to horror in 1939 with Son of Frankenstein that Universal’s fortunes shifted once again, meaning unequivocally that horror saved the ailing studio. Decades before the rise of the contemporary blockbuster in the 1970s, then, Universal’s horror pictures stood out as examples of what we would now describe as “tent-pole” productions.

By drawing upon gothic literature, adaptations and remakes were key in the genre’s formation, but Universal pushed the envelope further by producing films that remained branded with recognizable staples of the gothic tradition, while radically manoeuvring outside of the parameters of the source material, most notably with the Frankenstein films. Considered by many critics as the frontispiece of classic horror cinema, James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein was the first horror sequel in film history, setting out numerous codes and conventions that continue to characterise the genre contemporaneously, especially the central motif that the monster will rise again (and again, and again).

The second wave of horror pictures followed hot on the heels of Son of Frankenstein, although Universal moved from lofty A-picture budgets to B-movie economics. This second cycle, said to have lasted from 1939—1946, included the House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula “monster mash” films, a protean precursor to the “shared universe” model currently employed by Marvel Studios; and as the Universal monsters moved further into parody, the Abbott and Costello films. Other studios developed and deployed horror pictures during this second cycle, including Val Newton’s RKO, Colombia and the Poverty Row studios. Indeed, “all the major studios contributed to this cycle,” and “commentators believed they were witnessing an unprecedented boom in horror film production,” as Mark Jancovich put it.

The Universal Monster canon would recycle once more in the late 1950s and early 1960s with the inception of television and the rise of “Monster Culture.” As ‘monster kid,’ Henry Jenkins has written in a special issue of The Journal of Fandom Studies, “the Universal monster movies had been part of the large package of ‘Shock Theater’ Screen Gems sold to television stations in the 1950s and still in active use on second-tier local stations in the 1960s.” The publication of Forest J Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine signifed an emergent fan culture that sat around the TV set, dressing up as their favorite monsters and consuming merchandised elements, such as the Aurora model kits. In 1964, Universal produced TV comedy series The Munsters to capitalize on this new audience of baby boomers as horror become part of the domestic furniture.

In the United Kingdom during the same period, Hammer Film Productions, like Universal, tapped into the gothic tradition, with director Terence Fisher’s Dracula, The Curse of Frankenstein and The Mummy offering “the loveliest-looking British films of the decade,” several critically regarded film series (although such regard has been retroactively applied in many cases). Over time, the quality of Hammer’s output dipped, moving from serious, though melodramatic films, to absurdly camp—although that did not prevent the studio from winning the Queen’s Award for Industry in 1968 for managing to entice $4.5 million from North America and into the UK economy. This was the Golden Age of British Horror.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, literary adaptations once again became the life-blood of the genre, at least in part. Alfred Hitchcock’s translation of Robert Bloch’s Psycho led to the Director’s nomination for an Academy Award as well as Janet Leigh for Best Supporting Actress, for which she won the Golden Globe, and John L. Russell for Cinematography. And for many critics, Psycho set the groundwork for what would later become known as the “slasher film” in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. But it was the publication of Ira Levin’s neo-Gothic thriller Rosemary’s Baby in 1967 that would spark (apparently) a new Golden Age of horror cinema. Directed by Roman Polanski and starring Mia Farrow, the film adaptation of Levin’s neo-Gothic thriller was certainly controversial, with conservative critics and moralizers criticising the film for its “perverted use of fundamental Christian beliefs,” as recounted by David J. Skal in The Horror Show. This, however, didn’t prevent the film sweeping up a lion’s share of box office receipts in 1968, with Ruth Gordon winning the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, and a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. Gordon also won the Golden Globe in the same category, while Mia Farrow was nominated for Best Actress.

Following on from the success of Rosemary’s Baby, William Friedkin’s adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s novel, The Exorcist, was a cause célèbre, a film that was both excoriated and celebrated in turn. As Mark Kermode explains, The Exorcist was

written by a Catholic, directed by a Jew, and produced by the vast multinational Warner Bros., this was a movie that was championed by sometime political radicals such as Jerry Rubin, picketed by concerned pressure groups, paid for by millions of eager punters, praised by the Catholic News for its profound spirituality, and branded satanic by evangelist Billy Graham. Never before or since has a mainstream movie provoked such wildly diverging reactions.

The Exorcist demonstrated that horror cinema continued to be legitimately mainstream, becoming the second most popular film in 1974—after Paul Newman and Robert Redford vehicle, The Sting—and receiving nominations for ten Academy Awards, including Best Picture (the first horror movie to be nominated in that category) and Best Director, as well as eight Golden Globes, four of which it won (including the coveted Best Picture and Best Director). At the box office, The Exorcist became the highest-grossing horror film in history, and remains so to this day (more on that below).

In 1976, Brian De Palma adapted Stephen King’s debut novel, Carrie, starring Sissy Spacek and Pippie ‘dirty pillows’ Laurie. As explained in Simon Brown’s excellent Screening Stephen King, it was De Palma’s adaptation that catapulted King from horror fiction niche to household name as opposed to the novel itself. Carrie received Oscar nominations for Spacey and Laurie for Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress, respectively.

Adaptations were not the only dish on the horror menu, however. Richard Donner’s The Omen, also in 1976, earned over $60 million at the box office, garnering critical plaudits and Academy Award nominations for Best Original Score, which Jerry Goldsmith won. Further, Billie Whitlaw was nominated in the Best Supporting Actress category at the BAFTAS and won the Evening Standard British Film Award for Best Actress, while Harvey Stephens was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Acting Debut.

While not in the same league as The Exorcist in box office terms, Tobe Hopper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre converted a budget of $80K into $30 million—an ROI of 37,400%—thus demonstrating that films ostensibly created for the exploitation circuit could puncture the “heart of the mainstream,” just as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead managed to take $30 million in box office receipts on a budget of $114K in 1968.

The 1970s also became the petri dish for blockbuster/ franchise cinema, and it was a horror film that arguably started it all: Stephen Spielberg’s Jaws. Although George Lucas’ Star Wars would turn producers towards science fiction—even Bond went into space with Moonraker—Ridley Scott gave us sci-fi/ horror hybrid Alien in 1979. Yet, Jaws, Star Wars, and Rocky Balboa all engaged with serialization, more commonly known as ‘franchising.’ However, as discussed earlier, it was the Universal Monster canon that experimented with serialised filmmaking four decades earlier and should perhaps be viewed as early (or proto) franchising even though the term was not in use during the period, as Derek Johnson has emphasized. Horror cinema was not immune to the industrial turn to blockbusters and “sequelization” that started in the 1970s. George A Romero produced the first sequel in his Zombie continuity-less franchise, Dawn of the Dead, in 1979, while a year earlier, John Carpenter’s Halloween sparked what has been described as the ‘Golden Age of Slasher Movies,’ a cycle that is said to have existed between 1978 and 1984, comprising well-known films such as Friday the 13th, Prom Night and A Nightmare on Elm Street. Each of these films grew into powerhouse franchise properties, assisted by the rise of video in the 1980s, a medium that extended the life span of cinema from theatrical exhibition into the domestic realm, as well as introducing the capacity to, re-watch or record if broadcast on television. As with the Universal Monster canon, eighties’ monsters such as the stalk-and-slash triumvirate of Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, and Freddy Krueger, would return from the dead again and again, the ideal recipe for the franchise blueprint. Other characters emerged in the ‘80s as well that would lead to franchise development, including possessed doll Chucky from Child’s Play and Clive Barker’s demonic Pinhead from Hellraiser.

The 1990s horror film shifted, at least partly, towards psychological horror, with Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, an adaptation of Thomas Harris’ best-selling novel, winning the big five Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Adapted Screenplay. In mid-decade, Wes Craven’s final Freddy film A New Nightmare surprised critics with its smart meta-narrative, leading to Scream (1996) initiating a second Slasher cycle, but flavoured with postmodern commentary and self-conscious reflexivity. The success of Scream led to sequels Scream 2 (1997) and Scream 3 (2000), all of which spun box office gold—especially the first film, which made $170 million from a £15 million budget—as well as cycle films such as I Know What you Did Last Summer (1997), and Urban Legend (1998). In 1999, The Blair Witch Project popularised the found footage subgenre with a marketing campaign that has since gone down in history.

In the new millennium, the genre mutated once more (although I would insist that the genre has never quite been static). Spearheaded by the phenomenal success of James Wan’s Saw, the so-called “torture porn” cycle was born—more of an invention of the press than a discrete genre, as emphasized by Steve Jones—and over the next few years, explicitly violent films became part and parcel of mainstream cinema. The Saw franchise produced eight films over eight years, with the law of diminishing returns temporally halting production until the ninth part, Jigsaw, surfaced in 2017. This was the era of “the Splat Pack,” with ambassadors Rob ‘The Devil’s Rejects’ Zombie and Eli ‘Hostel’ Roth flying the flag for excessive splatter, gore and, in their own accounts, political transgression (see Mark Bernard’s brilliant monograph on the topic). Often admonished by the critical establishment, these films nevertheless became key elements of mainstream horror cinema and raided the box office.

The post-millennial landscape was also replete with remakes, reboots and re-adaptations, many of them coming from Michael Bay’s Platinum Dunes, ‘a remake house’ in all but name at that point. Described as “the deja-vu boom,” this convincingly shows that the genre need not be subservient to a single, univocal cycle but involves cross-breeding across and within sub-generic elements, a dialogic array of different manifestations of what we might describe as “horror” at any particular historic juncture.

In 2007, Jason Blum’s Blumhouse entered the scene, with found footage film Paranormal Activity setting box offices alight with a remarkable, record-breaking ROI. By converting a shoestring budget of 15K into box office receipts of $193 million, Paranormal Activity set the ground for what has become known as “micro-budget” horror filmmaking in the twenty-first century.

Paranormal Activity led to a further five films in the series between 2009—2014, but the second decade of the new millennium is also marked by a shift from extreme representations of gore and violence and back to atmospheric ghost stories, including the Insidious franchise, also from Blumhouse, and James Wan’s The Conjuring films and spin offs. This is not to suggest that so-called “torture porn” has disappeared, however: Pascal Laughier’s An Incident in Ghostland is certainly an intense ordeal as is the Australian film, Hounds of Love. Cycles wax and wane, but the genre is much more than this-or-that cycle at any given moment.

Are we experiencing a “new Golden age of horror films,” then? I certainly agree that the genre is in rude health at the moment, and that the Blumhouse economic model of “micro-budget” horror cinema is giving the majors a run for their money (so much so that I am researching Blumhouse for a monograph—tentatively titled Cheap Shots). But as this potted history shows—and it is very piecemeal, I admit—I definitely do not accept that horror cinema has been unquestionably fringe, unmistakably cult, emphatically marginal and wholly disparaged.

In 2017, Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Andy Muschetti’s re-adaptation of King’s IT were most often invoked as heralding the new Golden Age in press discourse, the former primarily because of the way in which it confronted the politics of race and was nominated for an Academy Award—certainly not the first to do either—and the latter because it shattered box office records for the highest-grossing horror film in history.

Except, it wasn’t. The common trend of citing economic performance without attending to inflation is patently ludicrous. In adjusted dollars, The Exorcist unarguably slaughters IT in no uncertain terms, standing at number one for horror cinema, and at number nine in all-time box office charts regardless of genre. Comparatively, IT stands at number 225. Moreover, The Exorcist out grossed every Star Wars movie, barring Lucas’ first instalment (now subtitled A New Hope).

As far as disparagement goes, it is more likely, I would argue, that it is popular cinema generally that is largely sneered at by the critical establishment, just as adaptations, sequels, remakes and franchising have been castigated as symptomatic of Hollywood’s creative inertia and decline. Many press accounts tend to deal explicitly in hyperbole of this sort, ignoring the history of cinema and the way in which adaptation and remaking practices have been with us since the very start, as pointed out by various scholars such as Constantine Verevis, Carolyn Jess-Cooke and Luzy Mazdon (to name a select few). But I wonder—and I don’t know the answer to this yet—if horror cinema has managed to attract as many critical plaudits and establishment trophies and nominations than other so-called “genre pictures”? How many science fiction films, for example, have been nominated for an Academy Award comparatively? If establishment awards are any indication of mainstream success, it is certainly true that superhero films lag far behind horror cinema in terms of the trophy cabinet.

Of course, I am not suggesting that Oscars, BAFTAs, Golden Globes etc., are signifiers of quality, but I use the cases above as a way to illustrate that horror cinema has cut across cultural distinctions at different historically contingent moments. Thus, rather than view ‘the horror film’ in binary terms, as either operating on the cultish fringe or sneaking surreptiously into the mainstream, the genre is much more expansive than dualisms of this kind allow. There is no such stable or concrete generic category as ‘horror,’ but a matrix of forces and factors that may account for the way in which the term has been discursively employed historically. To be sure, there are certainly aspects of horror cinema that have attracted a fair share of controversy and condemnation: from the Universal Monster cycle, The Exorcist, the so-called “video nasties,” the rape-revenge film, “torture porn,” The Human Centipede, The Bunny Game, A Serbian Film, etc. etc. But these currents and trends do not make up the genre that we understand as horror entirely. Horror cinema is neither wholly maligned or critically celebrated, but exists in a more complex and complicated array of dialogic utterances and discourses that often cuts across cultural distinctions.

I would also add that the proliferation of new media affordances such as streaming giants, Netflix and Amazon Prime, both of whom produce their own films and series, have dallied in horror, Mike Flanagan’s adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House on Netflix being a particularly fine example of serial horror (and the third adaptation of Jackson’s novel). But do these texts illustrate a “renaissance,” or a “new Golden Age”? Or are there simply more media platforms to populate with content? There is no way, I would argue, that the quantity—and quality—of horror series, serials and films being produced at the moment outweigh other cycles and currents in previous decades.

Over the next few weeks or so, Confessions of an Aca-Fan pays host to a new series comprised of interviews with several academics centred on aspects of cult media, horror, exploitation, the gothic, and more besides. And while the focus is not entirely on fandom, interested readers will no doubt recognise that the majority of these scholars could certainly fit in with the definition of what Henry Jenkins would describe as ‘aca-fandom,’ even if they do not identify as such themselves in direct terms. I asked similar questions of our contributors at times, while at others hone in on individual research endeavours, with the hope of producing a discursive debate of kinds.

We hope you enjoy the series and if anyone would like to contribute an essay or propose a topic, please email at bproctor@bournemouth.ac.uk.

William Proctor is Senior Lecture in Transmedia, Culture and Communication at Bournemouth University in the UK. He has published widely on various aspects of popular culture and is currently writing his debut monograph, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia (Palgrave). Along with co-editor Matthew Freeman, William has recently published the edited collection, Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth for Routledge. He can be reached at bproctor@bournemouth.ac.uk.