The Czech Zine Scene (Part 2): Science Fiction Fanzines

/In the Grey Zone of Science Fiction

By Ivan Adamovič

__________

The Birth of Fanzines Out of Desire and a Spirit of Possibility

Sci-fi literature was usually the domain of young men who were drawn towards exact technical sciences. Within one particular nest of such creatures, the college dorms of the Mathematical-Physical Faculty of the Charles University in Prague named Větrník (Windmill), one of the first and the most well-known Czech science fiction fan clubs was born, named Villoidus. It was established in 1979 by a group of students and centred around Zdeněk Rampas. Three years later, the club began to publish one of the first Czech sci-fi fanzines.

It happened like this: in 1980, the core founding members of the club went into their compulsory military service and leadership of the club was taken over by a second generation of members who were born in 1960: Jiří “Pyvos” Kuřina, Vladimír Wagner and Miloš “Albert” Podpěra. Kuřina and Podpěra shared a dorm room together, where they kept a sci-fi library for club members. According to Miloš Podpěra, it was during one evening meeting of the club that the idea of publishing a club magazine originated. That such a thing exists was learned from the only remaining member of the first generation of the club, Jiří Markus, who avoided military service due to health reasons and who had access to information sources about the outside sci-fi world. He had an excellent knowledge of English, which was uncommon at the time; he was the owner of an extensive English sci-fi book collection, and would sometimes read his translations of sci-fi novels during meetings. Sometimes he would even translate directly while reading the English original.

So, it was that this mathematician-physician Jiří told his friends that in English-speaking countries, fans publish their own “fanzines” (1). Everyone immediately wanted to publish their own fanzine too. From this moment on, and for the next few decades, Czech fandom adopted basic English terminology pertaining to fan activities—that is the terms fan, fandom, fanzine and con (convention—a meeting of fans). They used these expressions for more than10 years, as more specialised terms and acronyms weren't needed.

Other pieces of the puzzle came together quickly. In the autumn of 1981, Petr “Pagi” Holan returned from military service; he was a member of the faculty board of the SSM (Socialist Youth Movement). The leadership of the SSM welcomed any new activity that it could use to demonstrate its own activity, and so became the umbrella organization (2) for the fanzine. As with most things at the time, a combination of both official and unofficial procedures was needed. In April 1982, for the nationwide Parcon con, 150 copies of the first issue of the "Magazine for internal needs of SFK FO SSM UK / FMF" was published.

Just so that things are clear: the first periodical sci-fi fanzine was probably Sci-fi Věstník (newsletter), first published in January 1981 for members of the Teplice Observatory sci-fi club. It originally contained only short stories, which is why the publishers of the mathematical-physical Sci-fi magazine denied it the label “fanzine” in one of their editorial writings. Should we want to try to map even more obscure beginnings, then the first samizdat publication, bordering on a fanzine and an anthology was the Vega publication, which was published in Pilsen in 1977 as a supplement to the newsletter of the Předenice tramp settlement.

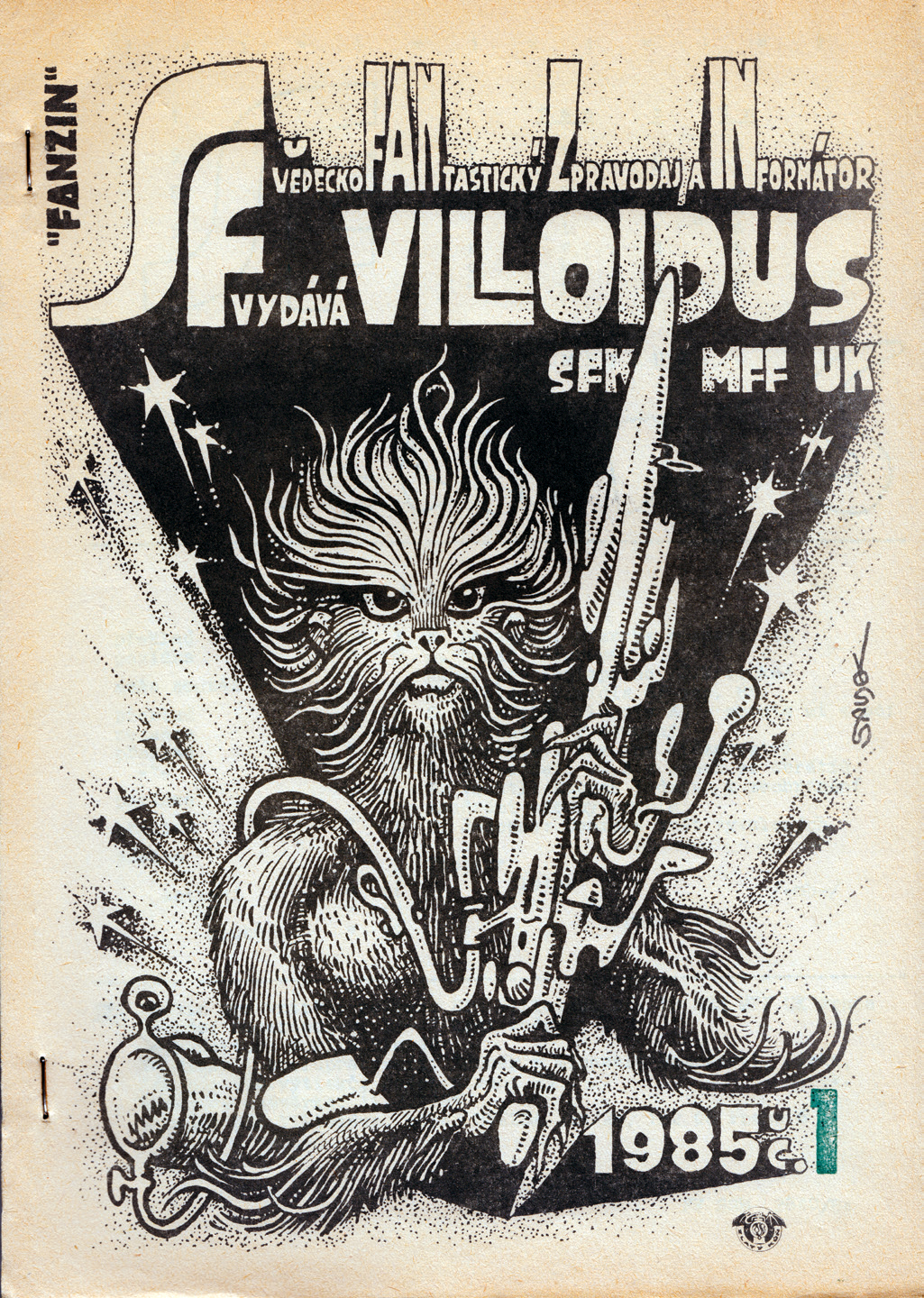

But let's get back to Prague mathematicians and physicists. Starting with the second issue, the term “magazine” was changed to “fanzin”. The editors didn't realise at first that a fanzine should have a name; there was a typographic logo “SCI-FI” on the cover, which was thought to be the name of the publication; it was later called by the club name: Villoidus. In 1983, a sub-title appeared: “VědeckoFANtastickýZpravodaj a INformátor” (Science Fiction Bulletin and Informer), which was a Czech backronym that attempted to explain the potentially dangerous Anglicism “fanzine”.

Official support from the authorities was a significant aid in the practical aspects of fanzine production (3). Typed cyclostyle stencils only needed to be taken to the university copying centre, which would then print the “internal periodical” in the desired number of copies. The content was most likely regularly checked for subversiveness, but no restrictions of content had ever taken place.

The fanzine content (4) was a mix of short stories translated mostly from English and Russian, original Czech stories, fandom news, literary competition results, overviews of sci-fi publications abroad, advice to novice authors, and of course, reviews.

Villoidus #1 1985 illustration: Kaja Saudek

Graphic-wise (5), the Sci-fi fanzine was fairly conservative; the cyclostyle copying process had its limitations as to the illustrations and graphics that could be reproduced, so apart from a few exceptions, the content was primarily text. From 1985, however, the fanzine featured an illustrated cover by the famous painter and comic book illustrator Kája Saudek. The drawing always depicted the club mascot in some form, the fictional Green Fleecy, whose Latin name Villoidus gave the club its name. The fanzine cover probably had the best appearance of all Czech fanzines at the time.

Over the course of a few years, the fanzine print run doubled to 300 issues. The fanzine stopped being published in the year 1989 (6). The editors, one by one, had finished their studies, and with the fall of the Communist regime, they now had incomparably wider options for self-realisation. The chief editor of the last two issues was Martin Klíma, who was involved in the student movement Stuha, and who on November 17, 1989 was one of the spokespeople of the student protests in Albertov in Prague at the beginning of the Velvet Revolution.

1. Fanzines

The first sci-fi fanzine is sometimes considered to be The Comet, published by the “Science correspondence club” in Chicago in 1930; however, The Time Traveller, published from 1932, is a better fit for what we understand a fanzine to be today, as The Comet mostly concerned itself with purely scientific matters. The expression “fanzine” has been use in English speaking countries since the beginning of the 1940s. It seems that it was first used to describe amateur publications specifically in the sci-fi genre. The genre's most significant fan award, Hugo, has been presented annually at the Worldcon convention since 1955 and offers an award for the category of Best Fanzine.

American and British fanzines were printed using similar techniques that would later be used for Czech ones. Initially, fanzines had a more serious tone; later on, their content concentrated more on fandom itself rather than published science fiction literature. This explains the general prevalence for rather cryptic humour and jargon—fanzines were primarily publications for an insider community.

In contrast to Czech fanzines, the fanzines in English speaking countries were often published by a single fan, who could obtain a significant “Egoboo”, (a boost of selfworth) by doing such a thing. Also in contrast to Czech fanzines, these fanzines moved away from publishing short stories; a more common occurrence was fan letter sections, a feature wholly absent in Czech fanzines. In some foreign magazines, the fan letter section was even the majority of content and served as a communication tool before the Internet came into existence. Letters from fans would react to other fan letters or to articles from the last issue, and were often written with the intention of obtaining a free copy of the next issue of given fanzine.

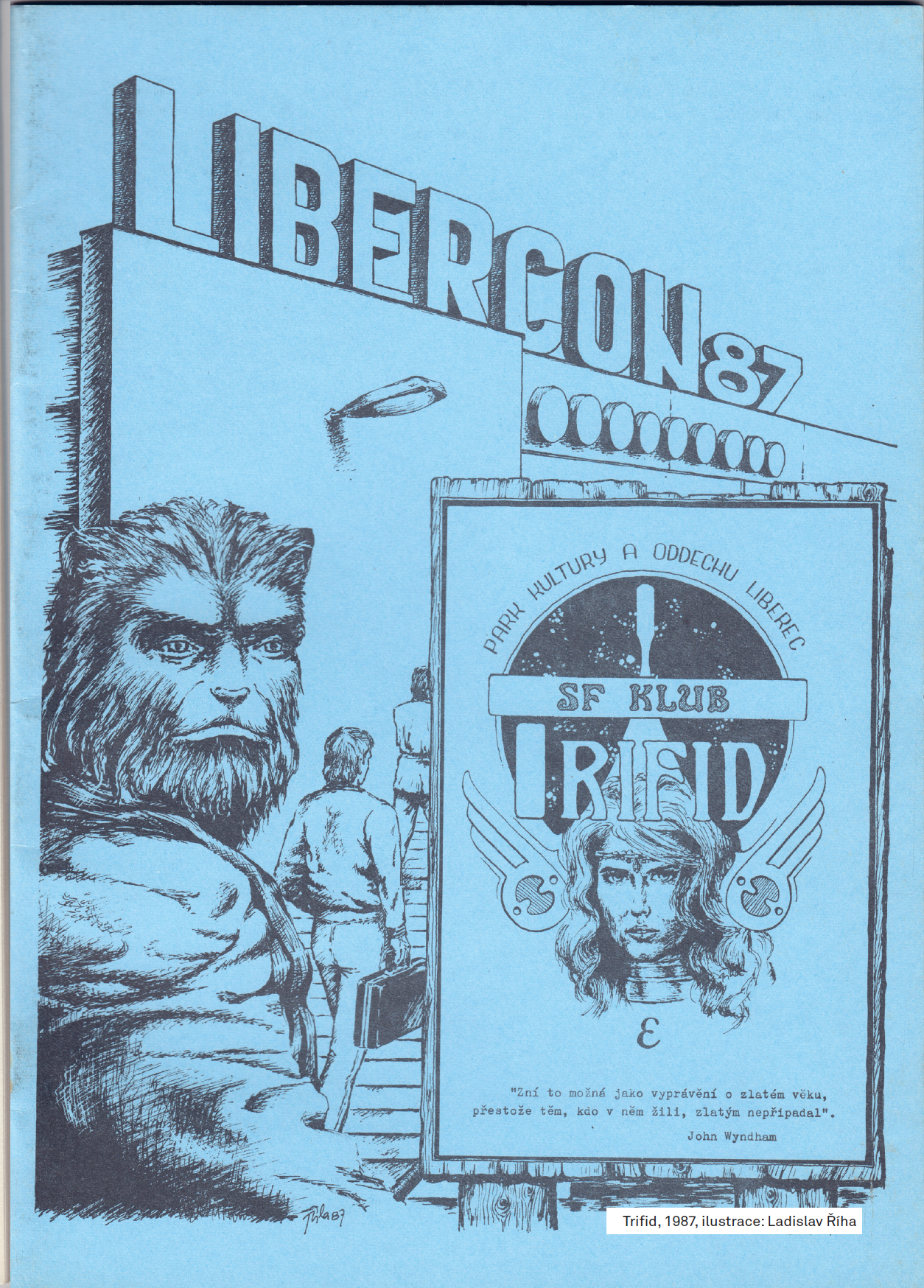

Trifid 1987 Illustration: Ladislav Riha

2. Umbrella Organisations

The vast majority of domestic, pre-revolution fanzines were published by science fiction clubs–and these practically always existed under an official organising institution. It was never stated that a club or a group had to have an official organising institution, but to have one's back covered during socialism spared the nerves of fans (in Poland, some science fiction samizdat publishers were investigated by the police for suspicion of economic crimes) and also the umbrella organization aided in the publication and distribution of club fanzines.

Even though they were “samizdat”, fanzines never didn't have content subversive to the regime present in them, nor did anyone feel any need for it. A rare exception was the R. E. Howard short story “Beyond the Black River”, published in the Poutník (Wanderer) fanzine, which had the Socialist Youth Movement organisation of the TOS Hostivař state company as an official organizer. The story was deemed too bloody and harsh to the local commissars. The fanzine then had to find an alternative official organiser institution, which became the Socialist Youth Movement of the Chemical-Technological University. There were also cases of deception being used: fanzine publishers would make up an organising institution, or would use the name of an existing one without this institution being aware of the fact that a club magazine was using their name as political cover.

3. Fanzine Production

Although fanzine production (that is, the printing and binding) wasn't particularly creative work, it was useful in bringing teams together. Some organising institutions had a reproduction section that took care of the printing; that is, unless supplies of blank paper or cyclostyle papers ran out and it was necessary to wait for delivery of new supplies. In other cases, fans had direct access to copying machines. It is worth noting that in the 1980s, copying machines were closely guarded and kept under strict control. This was due to the authorities' fear of politically subversive or generally uncontrolled publications.

An article by Milan Dundr, “Tisknu, tiskneš, tiskneme” (“I print, you print, we print”), published in fanzine Slan issue 2/1988, offers an insight into the intricacies of fanzine production. First, the operators of the process had to be selected. In the above-mentioned article, these were a person who swapped out copying sheets and applied paint onto the printing drums (and gradually got stained by paint himself in the process), a person who turned the printer crank or operated the printer motor, a person who put paper into the printer and tried in vain for the printer to take them up individually, and the very necessary quality controller, who checked the quality of the prints and scolded the aforementioned operators accordingly. After printing, another person sorted the pages into piles and removed any accidentally blank pages. Then everyone present went around the piles and took one paper from each until they had a complete issue in their hands. An especially important function was that of the person who bound the issues together after carefully checking the number and orientation of all pages.

The making of one issue of the Slan fanzine in this way took the fans about three afternoons (the fanzine had about 30 pages, 70 copies were printed). Printing one page 70 times took about 15–20 minutes at a leisurely pace. The fans attempted to speed up this process by setting up a contest for the fastest page print. This was carried out with much physical effort, accompanied by shouts of “Come on!”, “Rolling!”, “More paint!” or "Wipe it clean!". The fastest team was able to print all copies of one page in one and a half minutes. The effort rubbed off on the compilers and binders too, so the first issue of the 1988 Slan fanzine was produced in one evening meeting in three and a half hours.

Cyclostyle was the most common method of copying fanzines in the mid-1980s; however, there were also simpler, if more laborious, methods. Fans from the Karlovy Vary science fiction club Farma zvířat (Animal Farm) described a possible alternative in 1992: "We've found the intersection between our desires and our means in a printing technique which we've dubbed Rollset. Rollset is the cheapest printing method of all; you'll need a wooden frame with a screen, copying stencils, a roller, and paint. You put the inscribed stencil on the frame, apply paint evenly, place this on a blank piece of paper and then roll over it with a roller. If you've got enough stamina, you can print up to a thousand copies this way. (But you won't!)"

4. Fanzine Content

The content of fanzines was dependent on the resourcefulness and skills of individual science fiction club members. There were effectively two kinds of clubs. One was a club that was present in a certain location (a group of active fans in a specific place), the second kind was a club associated with a particular organisation (usually a university). There were exceptions to this, for instance more well-known fanzines such as Interkom, which was primarily a newsletter about goings on within Czechoslovak fandom, or R.U.R., whose club of the same name was considered to be the central Prague science fiction club, which stood above all other clubs.

Tresl #8 1994

It was apparent that fanzines were supplanting a non-existent magazine. Few good science fiction books were being published, so foreign short stories translated by club members was popular fanzine content. Clubs had differing capabilities in this respect, so for example the Poutník (Wanderer) fanzine published the first Czech translations of the Conan fantasy stories, translated by Jan Kantůrek; another club member produced shortened translations of complete novels, for example Isaac Asimov's Foundation. In the Villoidus fanzine, Czech readers learned of Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series approximately 10 years ahead of others, through extensive reviews with excerpts. Translations were often carried out via a third language, for example English science fiction from Russian or, more often, Polish. Novice Czech authors would sharpen their literary skills on fanzine pages; however, the best stories were usually submitted to the fandom competition for the Karel Čapek Award. Fanzines published practically all work from club members that was at least a little bit readable, so the overall content quality wasn't particularly great, but a few talented writers did appear, for example Jan Hlavička, the original Zdeněk Páv, or the radical Eva Hauserová, who termed her style “biopunk”.

What might seem as very bizarre to today's readers were reviews of contemporary films, some of which described in detail the plot of a film that could only be seen on video, for example, and which were thus completely inaccessible for an average fan. More news-oriented fanzines often published lengthy discussions, primarily about differing views on the running and organising of fandom (Vladimír Veverka, Jiří Karbusický, and Václav Pravda excelled in this), or about fanzines' missions (Láďa Peška). Reading these today, one can get easily the impression that fandom was more akin to a tiring conference than a fun hobby.

Similarly to authors of American fanzines, some of the local fanzine creators would later professionalise—the publisher of the Bene Gesserit fanzine (probably the first fanzine intended to be primarily sold) founded the Winston Smith publishing house, Tomáš Jirkovský turned his Laser fanzine into a notable publishing house of the same name. On the other hand, in terms of original content, there was practically no overlap in authors writing for fanzines and those writing for the general public, even after 1989.

After the first professional magazine Ikarie started publishing in March 1990 and fandom started to fragment into smaller interest groups, there was a shift to more purely fan fanzines and a more laid back approach to content. Ikarie itself was the transmutation of the Ikarie XB fanzine, which was probably the most ambitious project of Czech fandom. It had a group of experienced sf editors (Jaroslav Olša, Pavel Kosatík, Ondřej Neff, and Ivan Adamovič), was printed on quality paper using offset printing technologies (with a handmade template combining text written on an electric typewriter, hand-made, or transfer paper made headlines). The fanzine was inspired by the Polish magazine Fantastyka. When Ikarie began to be mass-published, fans still considered it a fandom magazine, which lead to a sense of disappointment in some who thought the editorship didn't co-operate with fandom much (in reality the magazine had a long-running regular section about fandom).

Since the beginning of the 1990s, fanzines were also being published that were devoted to a particular part of the fantasy genre, for example Terry Pratchett's Discworld (CoriCelesti), hero role-plays and table games (Dechdraka / Dragon's Breath), works of J. R. R. Tolkien (Imladris), the cyberpunk-influenced Poslední dávka (Last Dose; a transmutation of the R. U. R. fanzine), the heroic fantasy oriented Ghul, the Ducháček fanzine devoted to the horror genre, or purely personal fanzines that served only to publish the views and observations of a single author (for example Wild Shaarkah, produced in English by Eva Hauserová). One fanzine that has survived since the 1980s until now and remains probably the most significant fandom publication is the Interkom newsletter, directed by Zdeněk Rampas.

5. Graphic Design

The November 1989 revolution and the sudden liberalisation of information and trade didn't have a significant effect on fanzines at first. This also applies to the graphic aspect of these publications, which still had an amateur look well into the 1990s. The assumption that more and more fanzines would follow the more “professional” graphic style of Ikarie XB proved false. Probably the opposite was true: with the widespread publishing of professional periodicals, fanzine publishers could focus more on the meaning of the word “amateur”, derived in meaning from “lover”. Fanzines remained the domain of lovers of genres.

Some fanzines put to good use their close relationships with professional artists, who would draw cover pages free of charge. Teodor Rotrekl authored the covers of the Slan fanzine, Kája Saudek was the author of the Sci-Fi/Villoidus and Poutník fanzines and also had a special agreement with the Šumperk fanzines Vakukok and Knihovnička Vakukoku (Vakukok Library), which allowed them to publish reprints of his older comics. Comics appeared on fanzine pages only in rare cases; these would be primarily Makropulos (published in Šumperk by Lubomír Hlavsa) and Trifid (published in Liberec by Miroslav Schönberg and Vladimír Hanuš).

In the second half of the 1980s the majority of fanzines switched to offset printing, which allowed for better quality reproductions of illustrations and allowed for higher quality paper to be used. Cases of Xeroxed fanzines also became more common, especially with fanzines that had fewer pages. In the 1990s, many fanzines switched to A5 format and some also transformed into semi-professional magazines. Energy previously used for fanzine publishing was channeled into smaller individual publications, primarily translations of short stories and novels.

6. The End of Fanzines

In 1985, there were about 26 different fanzines being published; in 1990, the number (including ones no longer in publication) was approaching 50. Most of these stopped being published during the 1990s, even though a number of new ones sprung up. The reasons have already been mentioned: the ageing of fans and new possibilities after the revolution, and to a lesser extent the Internet.

“How many of our fanzines would be able to survive competing with one or two officially published sci-fi magazines? Fear the moment when the first Czechoslovak Sci-fi magazine is released! That moment will mark the beginning of the end for Czech fanzines”, wrote Ladislav Peška, the Slan fanzine chief editor, in March 1987.

It was really the emergence of the Ikarie magazine and later on others, rather than the expansion of the Internet, that caused a gradual drop in fanzine numbers, even though not in as straightforward way as Peška had predicted. There were very few Internet fanzines, in the sense of publishing of finished issues; the principal fanzine in 1995 was amber.zine, which wrote about science fiction and new technologies. Other web project like the ambitious Fanzine.cz, Sarden, or Fantasy Planet can be considered more as being portals.

Conclusion: Grey Zone Stalkers

Sci-fi fandom activities were apolitical in nature and its protagonists had very differing political preferences. Politics wasn't written about in fanzines, and if it was discussed in club meetings, it was usually done in a quiet corner of a room on a one-to-one basis. In the most thorough documentation of Czech sci-fi fanzines before November 1989, published by Jaroslav Olša Jr. in the Nemesis magazine (December 1996-January 1997), we can read the following: “Oppression created a bond between Eastern European fandom (not only within their respective countries, but also on an international level), which then became a unique subculture, which, by its existence itself, fought against a totalitarian regime—primarily by mobilising people and giving them what they were lacking—a means of self-realisation”.

Times change, however, and we tend to look at civic activities outside of official structures a bit differently today. The whole fanzine realm would not be possible without the existence of a “grey zone”, in which things are neither permitted nor prohibited, but are quietly tolerated because they aren't considered dangerous. According to recent historians, the most notable of which is Michal Pullmann, the grey zone did not function in opposition to the Communist regime, but in accordance with it. “Having calm conditions for work” and the development of harmless hobbies was one of the staple policies of president Husák era of so-called “normalisation”, put in effect after the Prague Spring of 1968 to quell any rebellious tendencies.

“It was necessary to ask the question whether the indifference of the Czech and Slovak population, fed by a turn of the majority of people towards their own private matters and to ‘calm life’ outside of Communist ideology and power, wasn't in the end a firmer pillar of stability for the regime than secret police and ideological manipulation”, Pullman writes in the 2017 anthology What was normalization? A study of late socialism (Co byla normalizace: Studie o pozdním socialismu): “Society in Communist dictatorship was more than just a passive object of oppression. People (…) used means that were available to them to attaining their non-ideological, "natural" life aims—studies, good work, a decent life, etc”.

The plethora of “hobby activities” that sprang up in the 1980s was such a two-sided contract with the regime. We give to you, you give to us. And so we're back at the onset of the Sci-fi fanzine, which the university Socialist Youth Movement could declare as performing youth-oriented work, while sci-fi youth got a chance to publish a magazine. There are many such examples. In 1985, Prague fans established a fruitful co-operation with the Union of Soviet-Czechoslovak Friendship in the form of audio-visual materials promoting Soviet science fiction. Few fans considered it an act of collaboration, but rather took quiet satisfaction in cases similar to this, considering them to be evidence of how one could outsmart the regime using its own weapons. But this was the public behaviour of the majority of citizens; fans considered themselves to be at least “islands of positive deviation”. A deeper reflection on this dichotomy is, however, something that Czech society is moving towards fairly slowly.

Umbrella Organisations

During the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, clubs/fanzines existed for example under:

The local SSM – Socialist Youth Movement Slaný Sci-fi club - Slan fanzine, permission for publishing granted by the People's Committee of the town Kladno

Andromeda club, Pilsen – Andromeda fanzine

District libraries: Karlovy Vary Animal Farm club - Big Bang

Fanzine and other titles: Opava Hepterida club – Labyrint fanzine

Local Youth Clubs:Ostrava Literary fantasy club - Leonardo

Fanzine: Šumperk Makropulos club/fanzine

ROH – Revolutionary Union Movement houses of culture

Möbius club – Mozek (Brain) fanzine, approved by the People's Committee of Jihlava

ROH committees at state companies

club/fanzine AF 167, Brno

Central cultural house of the state railway company

Prague R.U.R. club and fanzine

Base Svazarm – Union for co-operation with the army organisation

Prague Ada club – Ikarie XB fanzine

Associated workers' clubs

Česká Lípa Bonsai club/fanzine

řebíč Třesk club/fanzine

Parks of culture and rest Liberec Trifid club, registered as a hobby and arts club

Observatories:Teplice Sci-fi

-------------------------------

Ivan Adamovič (*1967) studied scientific information and library science at the Faculty of Arts of the Charles University in Prague. He was one of the founders of the science fiction monthly periodical Ikarie, where he served as a journalist and foreign prose editor from the magazine's inception in 1990 until 2007. As a science fiction fandom member, he led the Prague R. U. R. club and was the chief editor of the club's fanzine, later named Poslední dávka (Last Dose). In parallel to his work for Ikarie, he also functioned as a cultural editor in several other magazines and led the alternative magazine Živel (Element). He was the co-curator of the Planeta Eden: Svět zítřka v socialistickém Československu (Planet Eden: The World of Tomorrow in Socialist Czechoslovakia) exhibition (2010), and is the author of the Czech Literary Fantasy and Fiction Dictionary (1995). He contributed to the American science fiction magazine Locus. He holds a total of twelve Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror (SFHH) Academy awards, four of these as Best Sci-fi Editor, three for Theoretical Writing of the Year. In 2005, he received the award in recognition of his long-term work for the Science Fiction genre. Ivan's Planet Eden project has an English blog here: blog.edenfuture.com. He can be contacted at: ivan.adamovic@email.cz