Bringing Critical Perspectives to the Digital Humanities: An Interview with Tara McPherson (Part One)

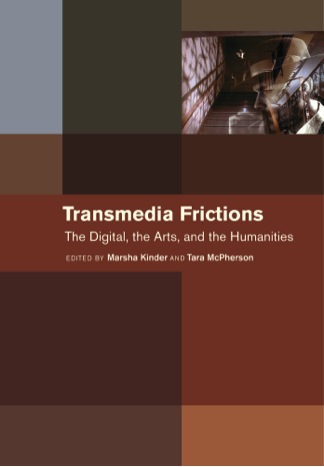

/Last week, I featured an extended interview with Marsha Kinder, reflecting on her new book, Transmedia Frictions, and on her lifetime of cutting edge thinking and production in the space of the digital humanities. This week, I am following up with a second interview with her co-editor on Transmedia Frictions, Tara McPherson, who describes how the 1999 Interactive Frictions conference has helped to shape her own work in the digital humanities. Tara's interview begins with a description of the kinds of collaboration and institutional support she received through the USC Cinema School. Since Tara's presence here was a big factor in my own decision to come to USC, this passage resonated especially strongly with me. It's hard to describe almost two decades of friendship and collaboration. The two of us connected when McPherson was a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and I was a young faculty member at MIT, having only recently completed my PhD at University of Wisconsin-Madison. I brought her to MIT for her first teaching job and from her time here, we joined with Jane Shattuc to edit Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, a book which was meant to identify and showcase the work of an emerging generation of cultural scholars (and has turned out to be pretty good at catching a bunch of current stars when they were on the rise.) When she left MIT to take up a permanent academic position at USC, we continued to collaborate helping to plan two conferences, one on each coast, exploring Race and Digital Spaces. And since I have come to USC, I've been able to deploy the Scaler platform which she helped to develop to build two online resources, one around Reading in a Participatory Culture, and the second around the forthcoming book, By Any Media Necessary. And of course, we've worked together on a range of dissertation and quals committees.

We have not always agreed, and our friendship is stronger for it. Her work starts from a more critical place than mine typically has, and as a consequence, she has taught me much through the years. Like any good friends, we can call each other out when we are wrong-headed, and when this is done in a constructive manner, it strengthens the friendship as well as the work that emerges from such conversations. She is one of the smartest thinkers I know about digital media, its potentials for humanistic scholarship, and especially about core issues around digital equity and diversity, which we need to keep in the forefront of our thinking. She has never been seduced by the shininess of the "new media" but has always sought ways to get underneath the hood, to know how it works, and to identify its consequences in a world already shaped by inequalities and injustices.

I am very happy today to be sharing this interview with a long-time collaborator and colleague.

Tell us about the 1999 Interactive Fictions conference. What were its aims? What do you see now, looking backwards, as its historical importance in the development of digital art and theory? How did it inform your own subsequent works in this area?

The opening of the catalogue copy from the exhibition – “Sparks. Heat. Conflict.” -- proved prophetic in many ways. There really was an amazing spark-filled energy at the event. Much of this energy came from the border crossing that the conference undertook: the mix of artists, industry folks, and scholars from several fields led to lively and provocative conversations. The late1990s was a period of incredible ferment for “new” media. This was the era of the full-on dot.com boom, and it was sometimes hard to see past the hype of Wired magazine and the denizens of Silicon Valley (or New York’s Silicon Alley or LA’s Silicon Beach.) We wanted to create an event that historicized this obsession with all that was “new” and that productively brought together those with a rich understanding of media history with those who were beginning to theorize the new forms of media that were so capturing the public imaginary. It was important then (and it remains important now) to situate digital media within a long historical framework.

In linking past and present, we also wanted to connect the study of new media with the political agendas that had so animated film theory across the decades. Conference co-organizers Marsha Kinder, Alison Trope and I were all deeply engaged in ideological critique, examining film and media through the lenses of gender, race, sexuality, and class. We didn’t want to lose this energy and sense of political commitment in the move toward digital media. We carefully selected keynote speakers, artists, and panelists whose own work took up these issues in order to foreground their importance to an emerging field. Another form of border crossing was generational. Marsha has always been a fantastic mentor to graduate students, and this undertaking was no exception. We included graduate students in the planning, in the exhibits, and in the panels in order to stage as diverse a set of conversations as possible. Now-established scholars like Mark Hansen, Wendy Chun, and Ian Bogost were all at the beginning of their careers in 1999 when they attended Interactive Frictions.

The conference had a profound effect on my own scholarly practice, as has the experience of teaching within a cinema school alongside artists and makers of many types of media. My training as a graduate student was as a theorist and writer with a strong focus on critique. My book, Reconstructing Dixie, draws from cultural studies and feminist theory to investigate the South’s role in the national imaginary and depends heavily on textual analysis. It did begin to engage new media but largely from the toolkits provided by my graduate coursework. I still value that training, but, in engaging digital media, I found that I needed to better understand its materiality. That is, in order to write about digital media, I needed to enrich my knowledge of how such media was made.

In the years leading up to the conference, I began to teach myself beginning production skills, enough to give me a basic literacy in design programs, HTML, and some computer languages. The conference sharpened my desire to extend this knowledge and also brought me into contact with several other scholars and artists who were beginning to work across the theory-practice divide. This has directly shaped the work that I have undertaken in the past fifteen years, first with the multimedia journal, Vectors, and later with the authoring platform Scalar.

It’s hard to imagine that I would have come to this work apart from the environment I’ve been in at USC, including the opportunity to work side-by-side with Marsha on the conference, where I learned from her example. Teaching in a cinema school has allowed me to observe first-hand the complexity of production. From feature and documentary films to experimental animation to video games, the site of production is multivalent and rich. I’m a better media scholar because I work in an environment where I interact each week with makers of media.

I also got to know future collaborators through the event, including Steve Anderson and Erik Loyer, both of whom I have now had the privilege of working with for over a decade. The border crossing that the conference modeled shapes my own collaborations today, collaborations that tend to extend across individuals with a diverse array of skills, talents and interests. While humanities scholars often collaborate (even as we are usually mostly rewarded for the work we do alone), we tend to work with other scholars who are similar to us, that is, with colleagues with similar methodologies and areas of study.

In the years since Interactive Frictions, I have, of course, undertaken collaborations such as these, but I suspect I have learned the most from my collaborations across difference, be they collaborations with technologists and programmers, with artists and designers, with librarians and archivists, or with community organizations. These types of collaborations require all involved to craft a shared vocabulary and to extend an intellectual generosity toward ways of knowing that might seem alien or opaque at first. But they can also be enormously generative and productive, if you learn to manage the heat and the sparks in useful ways!

From the start, the project of Interactive Frictions was to situate digital media in a more precise historical context, to connect contemporary projects back to their pre-digital precursors. To what degree do you think this project has been taken up over the past decade and to what degree do you see this book as still having to push us beyond a presentist focus on digital media as somehow without historical precedent in the kinds of changes it has wrought?

There is certainly an ongoing tendency to think of digital media as “new” media. This obsession with the new is built into the short shelf life of our digital devices, as the release of the latest version of the iPhone propels waves of consumerist frenzy. The temporalities of many social media practices also skew toward a presentism, encouraging our immersion in a kind of expanded, stretched-out now. This kind of always-on, perpetually-connected present dovetails neatly with the conditions of labor in late capitalism. Our devices and web platforms encourage us to stay connected all the time. Our email and our Twitter feeds always beckon. Our work time and our leisure time blur together. We write reviews on Yelp or Amazon, and our labor is harvested. On the one hand, this constant churn makes it hard to think historically; on the other hand, it’s all the more important that we do just that.

Scholars and artists have an important role to play here, calling our attention to the various ways in which today’s digital media both is and is not like earlier media forms. Emerging forms of immaterial and affective labor are relatively new, closely tied to the ascendancy of post-Fordist forms of capital. It’s crucial that we study what’s different about today’s labor patterns so that we can understand how they help support the growing income inequality and casualized labor practices that so shape our era.

The transformations of finance in the era of databases, simulations, and algorithms are significant and important, and we need to examine the differences between these forms of capitalism and those that categorized the industrial era. I find work of several scholars to be very helpful here, including David Golumbia, Trebor Scholz, Tiziana Terranova, and Lisa Nakamura. But that doesn’t mean that these patterns of immaterial labor or networked finance have nothing to do with earlier forms. A longer historical view will bring into sharper relief what really is changing and what continues on.

Transmedia Frictions clearly plots a longer historical arc for digital media. Many of the authors in the volume take great care in mapping both continuity and change, from Kate Hayle’s examination of print vs. code to Yuri Tsivian’s turn to early cinema to Eric Gordon’s focus on cityscapes. This longer historical framework also extends to the methodologies that contributors put into practice. For instance, Holly Willis takes up issues of feminism and embodiment in the work of new media artists, but her approach draws from and develops decades of feminist media theory. She attends with great care to the historical legacies of feminism for emerging media practices. These strategies can help us to resist the rush of the new and constant present of our increasingly digital lives.

Tara McPherson is Associate Professor of Critical Studies at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and Director of the Sidney Harman Academy for Polymathic Studies. She is a core faculty member of the IMAP program, USC’s innovative practice based-Ph.D., and also an affiliated faculty member in the American Studies and Ethnicity Department. Her research engages the cultural dimensions of media, including the intersection of gender, race, affect and place. She has a particular interest in digital media. Here, her research focuses on the digital humanities, early software histories, gender, and race, as well as upon the development of new tools and paradigms for digital publishing, learning, and authorship.

She is author of the award-winning Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Duke UP: 2003), co-editor of Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture (Duke UP: 2003) and of Transmedia Frictions: The Digital, The Arts + the Humanities (California, 2014), and editor of Digital Youth, Innovation and the Unexpected, part of the MacArthur Foundation series on Digital Media and Learning (MIT Press, 2008.) She is currently completing a monograph about her lab’s work and process, Designing for Difference, for Harvard University Press. She is the Founding Editor of Vectors, a multimedia peer-reviewed journal affiliated with the Open Humanities Press, and is a founding editor of the MacArthur-supported International Journal of Learning and Media (launched by MIT Press in 2009.) She is the lead PI on the new authoring platform, Scalar, and for the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture. Her research has been funded by the Mellon, Ford, Annenberg, and MacArthur Foundations, as well as by the NEH.